7. Multiplicative Functionals#

Authors: Jaroslav Borovicka, Lars Peter Hansen, and Thomas Sargent

Date: November 2025

\(\newcommand{\eqdef}{\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}}\)

Challenges in navigating long-term uncertainty.

Chapter 4:Processes with Markovian increments described additive functionals of a Markov process. This chapter describes exponentials of additive functionals that we call multiplicative functionals. We can use them to model stochastic growth, stochastic discounting, belief distortions and their interactions. After adjusting for geometric growth or decay, a multiplicative functional contains a martingale component that turns out to be a likelihood ratio process that is itself a special type of multiplicative functional called an exponential martingale. By simply multiplying random variables of interest by the multiplicative martingale prior to computing conditional expectations under a baseline probability, we compute conditional expectations under an alternative probability measure. The exponential martingale thus functions as a relative density that converts the baseline probability measure into the alternative probabability measure. For an early application of multiplicative functionals to asset valuation under preferences that express investors’ concerns about model misspecification, see [Anderson et al., 2003]. We will explore these and other applications in discussions that follow. We will see that multiplicative functionals have several applications. We shall use them study consequences of stochastic growth and stochastic discounting that persist over long time horizons and how macroeconomic shocks can have long-term impacts on asset prices. They provide a tractable modeling tool for studying models in which investors have subjective beliefs that can be described in terms of discrepancies from a baseline probability in ways that can be measured with statistical discrimination measures. We will also describe other applications of multiplicative functionals, including models of returns and positive cash flows that compound over multiple horizons, cumulative stochastic discount factors are used to long-horizon, and risk-return tradeoffs.

7.1. Geometric growth and decay#

To construct a multiplicative functional, we start with an underlying Markov process \(X\) that has a stationary distribution \(Q\), and we suppose that \(Y_0\) and \(X_0\) depend only on date zero information summarized by \({\mathfrak A}_0.\)

Definition 7.1

Let \(Y \eqdef \{ Y_t\}\) be an additive functional that as in Chapter 4 is described by

where \(X_t\) is the time \(t\) component of a Markov state vector satisfying \(X_{t+1} = \phi(X_t, W_{t+1})\) and \(W_{t+1}\) is the time \(t+1\) value of a martingale difference process (\({\mathbb E} \left(W_{t+1} \mid {\mathfrak A}_t \right) = 0 \)) of unanticipated shocks. We say that \(M \eqdef \{M_t: t \ge 0 \} = \{ \exp(Y_t) : t \ge 0 \}\) is a multiplicative functional parameterized by \(\kappa\).

An additive functional grows or decays linearly, so the exponential of an additive functional grows or decays geometrically. We construct a multiplicative functional recursively by

If we adopt adopt the normalization that \(N_t =1\) if \(M_t =0\), we can solve for \(N_{t+1}\)

In light of (7.1), we refer to \(N\) as the multiplicative increment of the process \(M\).

Chapter 4 stated a Law of Large Numbers and a Central Limit Theorem for additive functionals. In this chapter, we use other mathematical tools to analyze the limiting behavior of multiplicative functionals.

7.2. Special multiplicative functionals#

We define the three primitive multiplicative functionals.

Example 7.1

Suppose that \(\kappa = \eta\) is constant and that \(M_0\) is a Borel measurable function of \(X_0\). Then

This process grows or decays geometrically.

Example 7.2

Suppose that

Then

so that

A multiplicative functional that satisfies (7.2) is called a multiplicative martingale. We can view this process as a likelihood ratio process, so we’ll label it as \(M \eqdef L\). It will often be convenient to initialize this likelihood ratio process at \(M_0 = L_0 = 1.\)

Example 7.3

Suppose that \(M_t = \exp\left[f(X_t)\right]\) where \(h\) is a Borel measurable function. The associated additive functional satisfies

and is parameterized by \(\kappa(X_t, W_{t+1}) = h\left[ \phi(X_t, W_{t+1} ) \right] - f(X_t)\) with initial condition \(Y_0 = f(X_0)\).

When the process \(\{X_t\}\) is stationary and ergodic, multiplicative functional Example 7.1 displays expected growth or decay, while multiplicative functionals Example 7.2 and Example 7.3 do not. Multiplicative functional Example 7.3 is stationary, while Example 7.1 and Example 7.2 are not.

By multiplying together instances of these primitive multiplicative functionals, we can construct other multiplicative functionals. We can also on reverse that process by taking an arbitrary multiplicative functional and (multiplicatively) decomposing it into instances of our three types of multiplicative functionals. Before doing that, we explore multiplicative martingales in more depth.

7.3. Multiplicative martingales#

We can use multiplicative martingales to represent alternative probability models. We can characterize an alternative model with a set of implied conditional expectations of all bounded random variables, \(B_{t+1},\) that are measurable with respect to \({\mathfrak A}_{t+1}\). The constructed conditional expectation is

We want multiplication of \(B_{t+1}\) by \(N_{t+1}\) to change the baseline probability to an alternative probability model. To accomplish this, the random variable \(N_{t+1}\) must satisfy:

\(N_{t+1} \ge 0\);

\({\mathbb E}\left(N_{t+1} \mid {\mathfrak A}_t \right) = 1\);

\(N_{t+1}\) is \({\mathfrak A}_{t+1}\) measurable.

Property 1 is satisfied because conditional expectations map positive random variables \(B_{t+1}\) into positive random variables that are \({\mathfrak A}_t\) measurable. Properties 2 and 3 are satisfied because \(N\) is the multiplicative increment of a multiplicative martingale. Where

\(L = \{L_t\}{t=0}^\infty\) can be viewed as a likelihood ratio or Radon-Nikodym derivative process for the alternative probability measure relative to the baseline measure.

Representing an alternative probability model in this way is restrictive. For instance, if a nonnegative random variable has conditional expectation zero under the baseline probability, it will also have zero conditional expectation under the alternative probability measure, an indication that the implied probability measure is absolute continuous with respect to the baseline measure. Two models that violate absolute continuity can be distinguished with probability one from only finite samples. Likelihood-based statistical discrimination tests typically exclude such ``easy to distinguish’’ alternatives by assuming mutually absolutely continuous alternative probability models.

Representation (7.4) implies that the implied alternative conditional probability measure over \(\tau\) periods can be represented in terms of the likelihood ratio

which we can use to compute a \(\tau\) time-period-ahead conditional expectation. By using (7.5), we can compute a \(\tau\)-period conditional expectation by iterating on the one-period conditional expectations in accordance with the Law of Iterated expectations.

Multiplicative martingales provide a way to represent various models of subjective beliefs of private or government agents within dynamic, stochastic equilibrium models in terms of a statistical departure from a baseline model that the model builder uses to describe the data. [Hansen and Scheinkman, 2009] show that they also offer a way to value cumulative returns. Let \(R_t\) be a multiplicative process that measures a cumulative return between date \(t\) and date zero. Let \(S_t\) be a corresponding equilibrium discount factor between these same two dates. That \(L = RS\) is a multiplicative martingale follows from equilibrium restrictions on one-period returns. That is,

where \(S_{t+1}/{S_t}\) is the one-period stochastic discount factor and \(R_{t+1}/{R_t}\) is the one-period gross return. For the application, we construct

Here are some examples of multiplicative martingales constructed from some standard probability models.

Example 7.4

Consider a baseline Markov process having transition probability density \(\pi_o\) with respect to a measure \(\lambda\) over the state space \(\mathcal{X}\)

Let \(\pi\) denote some other transition density that we represent as

where we assume that \(\pi_o(x^+ \mid x) = 0\) implies that \(\pi(x^+ \mid x) = 0\) for all \(x^+\) and \(x\) in \(\mathcal{X}\).

Construct the multiplicative increment process as:

Example 7.5

Let an alternative model for a vector \(X\) be a vector autoregression:

where \({\mathbb A}\) is a stable matrix, \(\{W_{t+1} : t \ge 0 \}\) is an i.i.d. sequence of \({\cal N}(0,I)\) random vectors conditioned on \(X_0,\) and \({\mathbb B}\) is a square, nonsingular matrix. Assume that a baseline model for \(X\) has the same functional form but different settings \(({\mathbb A}_o, {\mathbb B}_o)\) of its parameters. Construct \(N_{t+1}\) as the one-period conditional log-likelihood ratio

Notice how the matrices \(({\mathbb A}_o, {\mathbb B}_o)\) of the baseline model and parameters \(({\mathbb A}, {\mathbb B})\) of the alternative model both appear.

Remark 7.1

Because \(\mathbb{B}\) is a nonsingular square matrix, model Example 7.5 has the same number of shocks, i.e., entries of \(W\), as there are components of \(X\). A more general setting would be a hidden Markov state model like one presented in Section Kalman Filter and Smoother of Chapter Hidden Markov Models that has a time-invariant representation with an ``information state vector’’ constructed as a way to condition on an infinite past of an observation vector.

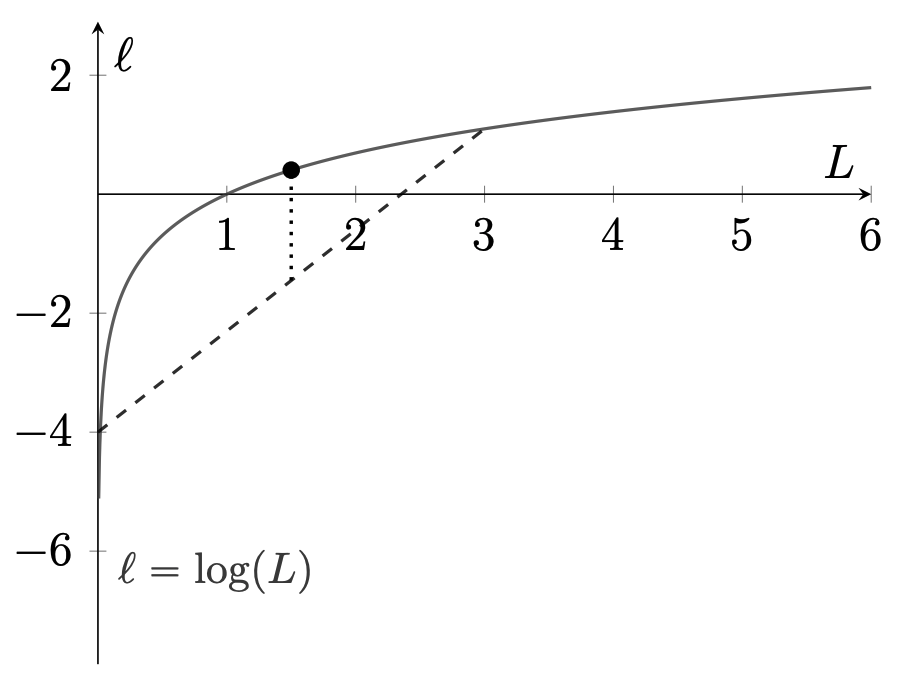

We can elicit a limiting behavior of multiplicative martingales by applying Jensen’s inequality to the concave function \(\log L\) depicted in Fig. 7.1 based on

where we normalize \(L_0 = 1\).

Fig. 7.1 Jensen’s Inequality. The logarithmic function is a concave function that equals zero when evaluated at unity. The line segment lies below the logarithmic function.An interior average of endpoints of the straight line lies below the logarithmic function.#

Moreover, by Jensen’s inequality,

for \(N_{t+1}\) satisfying \(L_{t+1}= N_{t+1} L_t.\). Note that

This implies that under the baseline model the log-likelihood ratio process \(L\) is a supermartingale relative to the information sequence \(\{ {\mathfrak A}_t : t\ge 0\}\).

From the Law of Large Numbers described Chapter 1:Laws of Large Numbers and Stochastic Processes , a population mean is well approximated by a sample average from a long time series. That opens the door to discriminating between two models. Under the baseline model, the log likelihood ratio process scaled by \(1/t\) converges to a negative number. If the baseline model actually generates the data, the expected log likelihood ratio constructed with data will eventually be negative except in the degenerate case in which \(N_{t+1} = 1\) with probability one. Such a calculation justifies discriminating between the two models by calculating \(\log L_{t}\) and checking if it is positive or negative. This procedure amounts to an application of the method of maximum likelihood. Sometimes

is used as a measure of statistical divergence.

Suppose now that we reverse the roles of the baseline and alternative probability measures.

Definition 7.2

The conditional relative entropy of a martingale increment is defined to be:

This entity is sometimes referred as Kullback-Leibler divergence. To understand why conditional relative entropy is nonnegative, observe that multiplication of \(\log N_{t+1}\) by \(N_{t+1}\) changes the conditional probability distribution for which the conditional expectation of \(\log N_{t+1}\) is calculated from the baseline model to the alternative model. The function \( n \log n\) is convex and equal to zero for \(n=1\). Therefore, Jensen’s inequality implies that conditional relative entropy is nonnegative and equal to zero when \(N_{t+1} = 1\)

conditioned on \({\mathfrak A}_t\).

Notice that

Thus \(L \log L\) is a submartingale. The expression

and is a measure of relative entropy over a \(t\)-period horizon. Relative entropy is often used to analyze model misspecifications and also appears in statistical characterizations used in information theory and large deviations theory for Markov processes (see [Cho et al., 2002]).

Remark 7.2

Consider the following example of likelihood-based model selection. Suppose that a decision-maker does not know whether a baseline or alternative model generates the data. Attach a subjective prior probability \(\pi_o\) to the baseline probability model and probability \(1 - \pi_o\) on the alternative. Let \(L\) be a likelihood ratio process with \(L_t\) reflecting information available at date \(t\). Date \(t\) posterior probabilities for the baseline and alternative probability models are:

When \({\frac 1 {t}} \log L_{t}\) converges to a negative number under the baseline probability, the first probability converges to one. But when \({\frac 1 {t}} \log L_{t}\) converges to a positive number under the alternative probability, the second probability converges to one. When the data are generated by the baseline probability model, the Law of Large Numbers implies the former; and when the data are generated by the alternative probability model, the Law of Large Numbers implies the latter. This shows that model selection based on posterior probabilities eventually selects the model that generated the data, i.e., either the baseline model or the alternative model. This analysis can be extended to situations in which some other model generates the data.

Remark 7.3

Martingales that represent changes of measure appear in asset pricing models that posit a difference between a representative investor’s ‘’subjective’’ model and a distinct model that a researcher or economic agents assume actually governs the data. Parts of the behavioral finance literature appeal to insights from psychology to motivate violations of that communism of beliefs axiom. Our tools can help us interpret such models by leading us to think about sources of those model discrepancies in terms of the understandings and motivations that might lead a sophisticated investor to acknowledge possible discrepancies between a subjective model and the type of baseline approximating model commonly used in asset pricing models. Using martingales to represent belief distortions allows us to frame topics in the behavioral finance literature. For example, to be intelligible, papers about over or under reactions must tell a reader with respect to what measure these reactions are to be judged to be mistakes. Our framework invites saying more about the martingale that accounts those over or under reactions. In some settings statistical divergence measures tell us that it is very difficult for sophisticated statisticians to distinguish or select among alternative approximating models as data descriptions. Investors’ belief distortions are likely to persist when statistical model-selection challenges confront both investors and the econometrician modeling them. We revisit these topics later in this chapter. See Section 7.7 and Section 7.9.

Remark 7.4

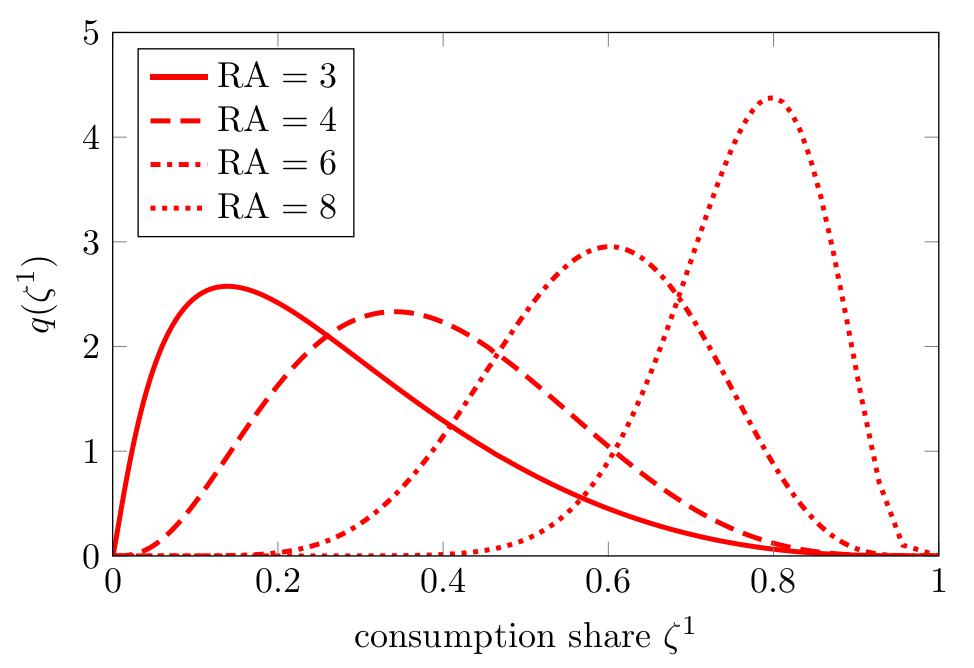

These tools are also pertinent to the study of models in which investors have heterogeneous beliefs. [Alchian, 1950] and [Friedman, 1953], among others, have argued that investors with distorted beliefs will eventually be driven out of the market by investors with more accurate perceptions of the future because of the relative success of the latter type of investors. This has been one argument for imposing rational expectations in asset pricing models. [Kogan et al., 2006] refine this view by breaking a simple link between survival and price impact of the investors with distorted beliefs. [Borovička, 2020] goes further by characterizing families of investor preferences for which the investors with the distorted beliefs survive in the long run. These latter two contributions feature differences in how investors look at stochastic growth. A continuous-time counterpart to the martingale representation for belief distortions that we describe and characterize in this chapter are featured in both the [Kogan et al., 2006] and the [Borovička, 2020] papers.

This figure is from [Borovička, 2020]. It plots the stationary densities for the fraction of aggregate consumption allocated to the first of two types of investors. The first is mistakenly optimistic about future consumption growth. The second knows the correct evolution. The figure illustrates that both consumers “survive” in the long run and that the allocation shifts in favor of the optimistic investor when both are more risk averse.

7.4. Factoring a multiplicative functional#

Following [Hansen and Scheinkman, 2009] and [Hansen, 2012], we factor a multiplicative functional into three multiplicative components having the primitive types Example 7.1, Example 7.2, Example 7.3.

As in definition Definition 7.1, let \(Y\) be an additive functional, and let \(M = \exp(Y)\). Apply a one-period operator \(\mathbb{M}\) defined by

to bounded Borel measurable functions \(f\) of the Markov state. By applying the Law of Iterated expectations, a two-period operator iterates \(\mathbb{M}\) twice to obtain:

with corresponding definitions of \(j\)-period operators \(\mathbb{M}^j\). The family of operators is a special case of what is called a ``semi-group.’’ The domain of the semigroup can typically be extended to a larger family of functions, but this extension depends on further properties of the multiplicative process used to construct it.

We next derive a revealing representation of this semigroup by factoring the multiplicative functional \(M\) in an interesting way. We achieve this by applying what is referred to in mathematics as Perron-Frobenius theory based on the following equation:

Eigenvalue-eigenfunction Problem: Solve

for an eigenvalue \(\exp(\tilde \eta)\) and a positive eigenfunction \({\tilde e}\).

Consistent with Perron-Frobenius theory, call the positive eigenvalue, the principal eigenvalue, and the associated positive eigenvector, the principal eigenfunction, of the operator \(\mathbb{M}\).

Use the principal eigenvalue and eigenvector, and define:

Note that we constructed \({\widetilde N}_{t+1}\) so as to have a conditional expectation equal to unity. Using \({\widetilde N}\) as a martingale increment process, build

Theorem 7.1

Let \(M\) be a multiplicative functional. Suppose that the principal eigenvalue-eigenfunction problem has a solution with principal eigenfunction \({\tilde e}(X)\). Then the multiplicative functional is the product of three components that are instances of the primitive functionals in examples Example 7.1, Example 7.2, and Example 7.3:

where \({\widetilde L}_t\) is a multiplicative martingale with \({\widetilde L}_0 = 1\).

The factorization of a multiplicative functional described in Theorem 7.1 is a counterpart to the Chapter 4 Proposition 4.1 decomposition of an additive functional. We used the Proposition 4.1 martingale to identify the permanent component of an additive functional in Chapter 4. In this chapter, we shall use the multiplicative martingale isolated by Theorem 7.1 to represent a change of probability measure, one that will help us understand long-term risk return tradeoffs. While \({\widetilde L}\) is a multiplicative martingale, \(\log {\widetilde L}\) is a super martingale. There is a weaker connection between the two representations, however. Write the additive decomposition as:

where \({\widehat L}\) is an additive martingale. As [Hansen, 2012] argues, if \({\widetilde L}\) is not degenerate (not equal to one), then \({\widehat L}^s\) is not degenerate (not equal to zero) and conversely.

Models in which \(X\) is a finite-state Markov chain are give a direct computation in which the principal eigenvalue calculation reduces to finding an eigenvector of a matrix with all positive entries.

Example 7.6

The stochastic process \(X\) is governed by a finite-state Markov chain on state space \( \{ {\sf s}_1, {\sf s}_2, \ldots, {\sf s}_n \}\), where \(s_i\) is the \(n \times 1\) vector whose components are all zero except for \(1\) in the \(i^{th}\) row. The transition matrix is \({\mathbb P},\) where \({\sf p}_{ij} = \textrm{Prob}( X_{t+1} = {\sf s}_j | X_t = {\sf s}_i)\). We represent the Markov chain as

where \({\mathbb E} (X_{t+1} | X_t ) = {\mathbb P}' X_t \), \({\mathbb P}'\) denotes the transpose of \({\mathbb P}\), and \(W_{t+1}\) is an \(n \times 1\) vector process that satisfies \({\mathbb E} ( W_{t+1} | X_t) = 0 \), which is therefore a martingale-difference sequence adapted to \(X_t, X_{t-1}, \ldots , X_0\). Think of \(W_{t+1}\) as the vector of errors when forecasting \(X_{t+1}\) based on current information.

Let \({\mathbb G}\) be an \(n \times n\) matrix whose \((i,j)\) entry \({\sf g}_{ij}\) is an additive contribution to the growth that \(Y_{t+1} - Y_t\) experiences when \(X_{t+1} = {\sf s}_j\) and \(X_t = {\sf s}_i\). The stochastic process \(Y\) is governed by the additive functional

Let \(M= \exp(Y)\). Define a matrix \({\mathbb M}\) whose \((i,j)^{th}\) element is \({\sf m}_{ij} = \exp({\sf g}_{ij}).\) Represent the stochastic process \(M\) as the multiplicative functional:

Associated with this multiplicative functional is the principal eigenvalue problem

To convert this to a linear algebra problem, write the \(j^{th}\) entry of \({\tilde e}\) as \({\tilde e}_j\). Since \(X_t\) always assumes the value of one of the coordinate vectors \({\sf s}_i, i =1, \ldots, n\),

when \(X_t = {\sf s}_i\) and \(X_{t+1} = {\sf s}_j\). This allows us to rewrite the principal eigenvalue problem as

or

where \(\widetilde {\sf m}_{ij} \eqdef {\sf p}_{ij} {\sf m}_{ij}\) and \({\tilde e}_i\) is entry \(i\) of \({\tilde e}\).

Notice that this construction incorporates the transition probabilities into the construction of the matrix \({\widetilde {\mathbb M}}\). We do this to reduce the problem to one of finding an eigenvalue and corresponding eigenvector of a matrix. Specifically, we want the positive eigenvalue associated with a positive eigenvector of (7.11).

After solving the principal eigenvalue problem, we construct an alternative transition matrix for a finite-state Markov process. Construct

and form the matrix \({\widehat {\mathbb N}} = [{\widehat {\sf n}}_{ij}]\). The matrix \({\widehat {\mathbb N}}\) has entries that are nonnegative, and

which verifies that \({\widehat {\mathbb N}}\) can be viewed as a transition matrix.

Finally, we show how to construct the factorization of the \(M\) process. To build the martingale of interest, we must undo the probability scaling that we did when forming \({\widehat {\mathbb N}}.\) With this in mind, solve for \({\tilde n}_{ij}\) that satisfies:

where we arbitrarily set \({\tilde n}_{ij}\) equal one when \(p_{ij} = 0\) and build the matrix \({\widetilde {\mathbb N}} = [ {\widetilde n}_{ij}]\). These constructions allow us to write (7.10) as

Remark 7.5

In the previous example, the matrix \(\widetilde {\mathbb M}\) could be inferred from prices of one-period-ahead Arrow securities. Specifically, given prices of all of the state contingent claims for next period, we can infer the column of \(\widetilde {\mathbb M}\) associated with the current state. By observing prices for all of the current states, all of the columns of \(\widetilde {\mathbb M}\). We only need to know \(\widetilde {\mathbb M}\) to pose and solve the principal eigenvalue problem and hence to construct transition probabilities as given by (7.12), but not the \({\sf p}_{ij}\)’s and the \({\sf s}_{ij}\)’s. This gives us a way to. recover a transition probabilities from asset prices in the language of [Ross, 2015]. Notice, in particular, that the \({\sf p}_{ij}\)’s and \({\sf s}_{ij}\)’s cannot be inferred uniquely from the \({\sf m}_{ij}\)’s. In particular, the Arrow prices are insufficient to identify the transition probabilities. Ross imposed restrictions on \({\sf s}_{ij}\)’s that implied that the recovered probabilities are actually the \({\sf p}_{ij}\)’s. In general, the recovered probabilities will differ from the baseline transition probability matrix. We will have more to say about this difference and investigate why the recovered probabilities remain interesting. See [Borovička et al., 2016] for an extended discussion of this claim.

The following log-linear, log-normal specification displays relevant mechanics of the multiplicative factorization with direct connection to the corresponding additive decomposition

Example 7.7

Consider a stationary \(X\) process and an additive \(Y\) process described by the VAR

where \({\mathbb A}\) is a stable matrix and \(\{ W_{t+1} : t \ge 0 \}\) is a sequence of independent and identically normally distributed random vectors with mean zero and covariance matrix \({\mathbb I}\). In Proposition 4.1 of Chapter 4, we described the decomposition

where

Let \(M_t = \exp(Y_t)\). Use equation (7.14) to deduce

where

and

While the additive martingale of \(Y= \log(M)\) has a variance that grows linearly over time, this variance contributes a component to the exponential trend of the multiplicative functional \(M\) along with a simple time-horizon adjustment to the martingale component.

Example 7.8

Consider the following stochastic volatility example. Suppose that a scalar state variable evolve as first-order autoregression:

where \(\{W_{t+1} : t \ge 0 \}\) is an iid sequence of normally distributed random variables. The state variable \(X_t\) gives the source of volatility fluctuations. Guess a principle eigenfunction of the form:

and construct

Write the principle eigenfunction equation as:

where we took logarithms of both sides of the equation. The computation on left side of this equation has a tractable formula for expressing the outcome as a quadratic function of the state.

Solve the equation in three steps. First, equate coefficients on \(x^2\) and deduce a quadratic equation for \(\epsilon_2.\) Next, equate coefficients on \(x\) and obtain a linear equation for \(\epsilon_1\). Finally, equate constants obtain an equation for \({\tilde \eta}\). The initial quadratic equation is

When it has a solution, there is will typically be two possible choices. For the solution to be of interest, \(1 - \epsilon_2 {\sf b}^2\) must be positive.

Second, equate coefficient on \(x\) to solve an equation for \(\epsilon_1\) given \(\epsilon_2\):

Third, we solve for \({\tilde \eta}\) by equating the constant and plugging the solutions for \(\epsilon_1\) and \(\epsilon_2\):

For this example,

where \(\propto\) means proportional to up to a scale factor that depends on \(X_t\). Under the implied change in measure, \(W_{t+1}\) is distributed as normal random variable with conditional mean

and precision \(1 - \epsilon_2 {\sf b}^2\). Under the change of probability measure, \(W_{t+1}\) remains normally distributed with a different variance and state-dependent mean. Under this change in probability measure, the \(X\) remains a first-order autoregression but with different dynamics. It could, for instance, be an explosive autoregression.

Remark 7.6

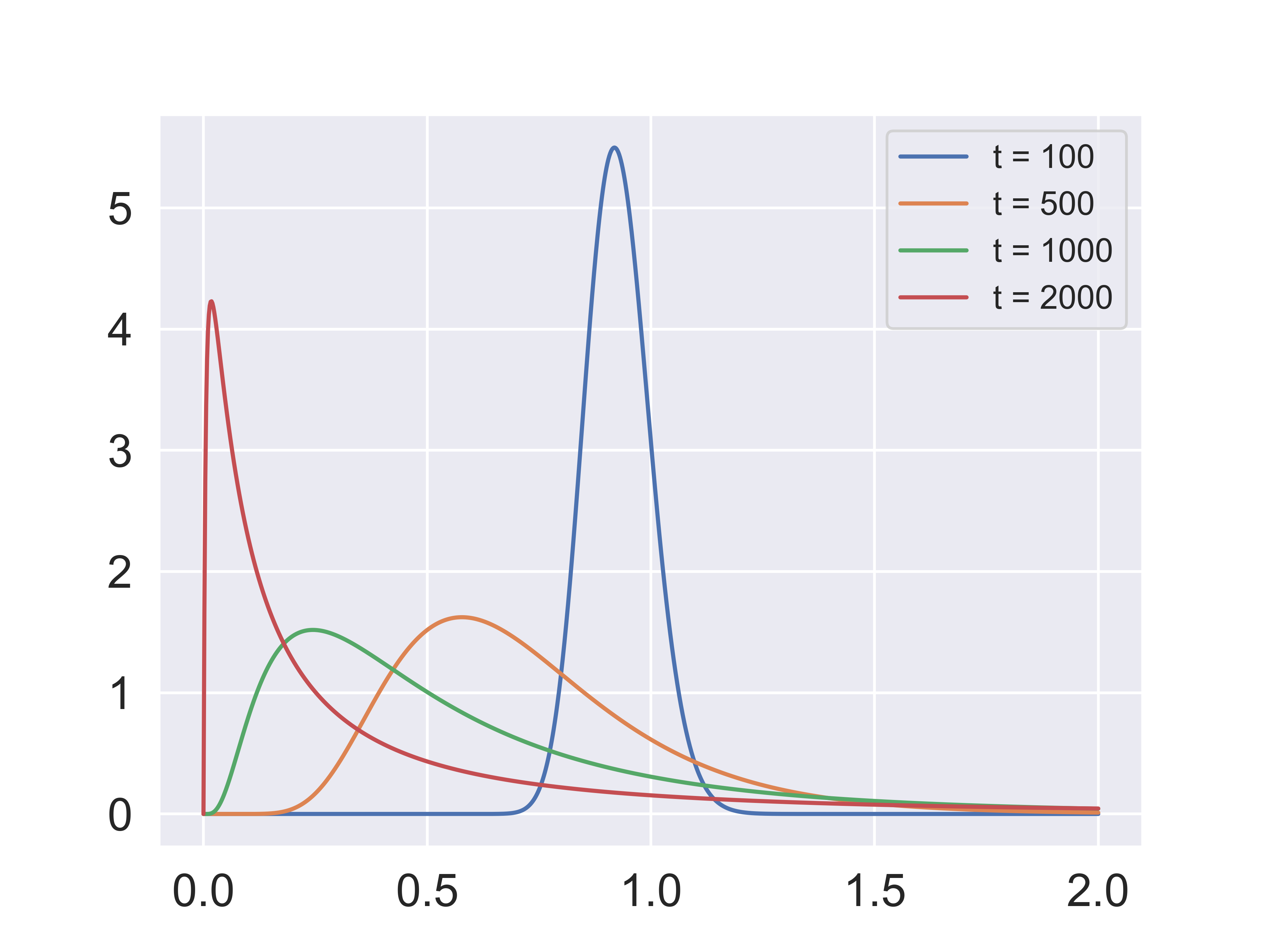

The martingale component of the multiplicative functional has “peculiar behavior.” It has expectation one by construction. The Martingale Convergence Theorem guarantees that sample paths converge, typically to zero. This theorem is operative because the positive martingale is bounded from below. Since its date zero conditional expectation is one, for long horizons this process necessary has a fat right tail. Fig. 7.2 plots probability density functions of the martingale component for different values of \(t\).

Fig. 7.2 Density of \(\widetilde{L}_t\) for different values of \(t\).#

Remark 7.7

Consider a positive cumulative return process, \(R,\) modeled as a stochastic functional. As we noted previously, for such a process, \(R_t/R_\tau\) for \(\tau < t\) is a \(t - \tau\)-period return for any such \(t\) and \(\tau\). Consider also the associated cumulative stochastic discount factor process, \(S,\) which we also take to be a multiplicative functional. For this process, \(S_t/S_\tau\) for \(\tau < t\) is the \(t - \tau\)-period stochastic discount factor for any such \(t\) and \(\tau\). Normalize \(R_0 = 1\) and \(S_0 = 1\). Repeating what we stated previously, by standard asset pricing logic, SR is a multiplicative martingale. [Martin, 2012] studies tail behavior of cumulative returns. Since its date zero conditional expectation is one, for long horizons this process necessary has a fat right tail as illustrated by Fig. 7.2.

While the multiplicative martingale has peculiar sample path properties, we are primarily interested in this martingale component as a change of probability measure. For instance, in Example 7.7, formula (7.15) for \({\widetilde N}_t\) tells how the change in probability measure induces mean \( {\mathbb H}\) in the conditional distribution for the shock \(W_{t+1}\). Similarly, \({\widetilde {\mathbb L}},\) with entries given in formula (7.12), provides an alternative transition matrix in Example 7.6.

7.5. Stochastic stability#

Our characterization of a change of probability measure as the solution of a Perron-Frobenius problem determines only transition probabilities. Since the process is Markov, it is of interest to seek an initial distribution of \(X_0\) under which the process is stationary and satisfies a stochastic stability property that we will define and explore. Stochastic stability opens the door the study of a variety of limiting behavior and hence justifies our interest in the multiplicative factorization. The eigenfunction problem can have multiple solutions, it turns out, however, that there is a unique solution for which the process \(X\) is stochastically stable under the implied change of measure. See [Hansen and Scheinkman, 2009] and [Hansen, 2012] for formal analyses of this problem in a continuous-time Markov setting. In what follows we investigate the discrete-time counterpart to their investigations.

Definition 7.3

A process \(X\) is stochastically stable under a probability measure \({\widetilde {Pr}}\) if it is stationary and \(\lim_{j \rightarrow \infty} {\widetilde {\mathbb E}} \left[f(X_j) \mid X_0 = x \right] = {\widetilde {\mathbb E}} \left[ f(X_0) \right]\) for any Borel measurable \(h\) satisfying \({\widetilde E} \vert f(X_t) \vert < \infty\).

As we discussed previously, a multiplicative martingale \(L\) with \(L_0 =1\) induces a probability measure conditioned on \(X_0.\) To check for stochastic stability, we extend the probability by including a distribution over \(X_0\) in a manner that ensure the process \(X\) is stationary.

Remark 7.8

Notice that the stationary probability distribution for \(X_t\) implied by \(\widetilde {Pr}\) is used to defined the limits of conditional the conditional expectations. For the mathematical results, however we initialize the distribution over \(X_0\) is not crucial. Thus we could equivalently consider other probabilities measures for which the same limiting distribution for \(X_t\) as \(t\) gets large. Under such probability measures, the process \(X\) would be asymptotically stationary. In this sense, we impose the stronger stationarity restriction as a matter of convenience.

Theorem 7.2

Let \(M\) be a multiplicative functional. Suppose that \((\tilde \eta, \tilde e)\) solves the eigenfunction problem and that under the change of measure \(\widetilde{Pr}\) implied by the associated martingale \(\widetilde L\) the stochastic process \(X\) is stationary and ergodic. Consider any other solution \((\eta^*, e^*)\) to eigenfunction problem with implied martingale \(\{ L_t^* \}\). Then

\(\eta^* \ge \tilde \eta\).

If \(X\) is stochastically stable under the change of measure \(Pr^*\) implied by the martingale \(L^*\), then \(\eta^* = \tilde \eta\), \(e^*\) is proportional to \(\tilde e\), and \(L^* = \widetilde L\) for all \(t=0,1,... \).

Proof

First we show that \(\eta^* \ge \tilde \eta\). Write:

Thus,

If \(\tilde \eta > \eta^*\), then

But this equality cannot be true because under \(\widetilde{Pr},\) \(X\) is stochastically stable and \(\frac {e^*}{\tilde e}\) is strictly positive. Therefore, \(\eta^* \ge {\tilde \eta}.\)

Consider next the case in which \(\eta^* > \tilde \eta\). Write

which implies that

Thus,

Suppose that \(\tilde \eta < \eta^*\), then

so that \(X\) cannot be stochastically stable under the \(Pr^*\) measure.

Finally, suppose that \(\tilde \eta = \eta^*\) and that \(\frac {\tilde e(x)}{e^*(x)}\) is not constant. Then

and \(X\) cannot be stochastically stable under the \(Pr^*\) measure.

Stochastic stability under the martingale-induced change of measure provides a way to frame some interesting long-term approximations. Let

where \({\widetilde L}\) is the martingale component in the factorization of \(M\). Construct the operator:

where we have use the factorization of \(M\). Form the family (semi group) of operators:

where we used the factorization given by Theorem 7.1 and the unique selection of such a representation Theorem 7.2 to obtain the right-side equaltty. Since \(X\) is stochastically stable under \(\widetilde{Pr}\),

for all \(f \in {\mathcal F}( {\widetilde L})\). In particular,

for \(f = \tilde f \tilde e\) provided that \(\tilde f \in {\mathcal F} ({\widetilde L} ).\) Observe that the division by \({\tilde e}\) when constructing \({\tilde f}\) absorbs the transient contribution to the factorization of \(M\):

We use limit (7.17) to justify calling the Perron-Frobenius eigenvalue as the long-term growth or decay rate of the multiplicative functional.

Under the stochastic stability restriction, we obtain a more refined approximation by adjusting for the growth or decay in the family of operators:

where we assume that \({\tilde f} = f/ \tilde e\) is in \({\mathcal F}({\widetilde L})\). Thus once we adjust for the impact of \({\tilde \eta}\), the limiting function is proportional to \({\tilde e}\). The function \(f\) determines only a scale factor \({\widetilde {\mathbb E}}\left[{\frac {f(X_t)} {{\tilde e}(X_t)}}\right] \tilde e(x)\).

We will apply the limiting results in a variety of ways in this and subsequent chapters. The multiplicative factorization can help us understand implications of stochastic equilibrium models for valuations of random payout processes. In addition, such factorizations can help organize empirical evidence in ways that make contact with such stochastic equilibrium asset pricing models.

7.6. Inferences about permanent shocks from asset prices#

Macroeconomists often study dynamic impacts of shocks to systems of variables measured in logarithms. For example, [Alvarez and Jermann, 2005] suggest looking at asset prices using a multiplicative representation of a cumulative stochastic discount factor, though without the tools provided by this chapter. The additive decomposition derived and analyzed in Chapter 4 is a convenient tool for identifying permanent shocks A prominent multiplicative martingale component implies a prominent role for permanent shocks in the underlying economic dynamics. A formal probability model lets us link an additive decomposition as described in this chapter and Chapter 4 to the multiplicative factorization that we study in this chapter. Log normal models, at least as approximations, are often used by applied macroeconomists. Example 7.7 provides an example with explicit formulas linking the two representations. While distinct, the two martingales, in this special case, are closely linked. In general, the connection is more subtle. In what follows we describe how a multiplicative martingale component to as stochastic discount factor is reflected in asset prices.

Consider stochastic discount factorization

where \(S_0= L_0^s = 1.\) A date zero price of a long-term bond is:

Compute the corresponding yield by taking \(1/t\) times minus the logarithm:

Provided that

the limiting yield on a discount bond is \(- \eta^s.\)

Next consider a one-period holding period return on a \(t\) period discount bond:

Using stochastic stability and taking limits as \(t\) tends to \(\infty\) gives the limiting holding-period return:

A simple calculation shows that \(R_1^{\infty}\) satisfies the following equilibrium pricing restriction on a one-period return:

These long-horizon limits provide approximations to the eigenvalue for the stochastic discount factor and the ratio of the eigenfunctions.

In a model without a martingale component, [Kazemi, 1992] observed that the inverse of this holding-period return is the one-period stochastic discount factor. Within the [Kazemi, 1992] setup, \((R_1^\infty)^{-1}\) equals the one-period stochastic factor. Let \(Y_1\) be a vector of asset payoffs and \(Q_0\) be the corresponding vector of prices. Then standard asset pricing theory implies the conditional moments restriction

[Alvarez and Jermann, 2005] extend this insight by showing that the reciprocal reveals the component of one-period stochastic discount factor net of its martingale component.

Remark 7.9

In practice, we have only have bond data with a finite payoff horizon, whereas the characterizations [Kazemi, 1992] and [Alvarez and Jermann, 2005] use bond prices with a limiting payoff horizon. Empirical implementations using such characterizations assume that the observed term structure data have a sufficiently long duration component to provide plausible proxy for the limiting counterpart.

7.7. Digression on rational expectations#

Under a rational expectations assumption, a researcher equates the baseline probability measure to be the one implied by the equilibrium of the model. The model of [Kazemi, 1992] provides an example. Kazemi’s underlying baseline model is Markov. Kazemi assumes that economic agents living inside his model are completely confident that they know those Markov dynamics. He thus adopts a rational expectations assumption. As noted by [Lucas, 1987] (p.13)

The term ‘rational expectations’, as Muth used it, refers to a consistency axiom for economic models, so it can be given precise meaning only in the context of specific models. I think this is why attempts to define rational expectations in a model-free way tend to come out either vacuous (‘People do the best they can with the information they have’) or silly (‘People know the true structure of the world they live in’).

Once we add the assumption that our model-implied expectations actually generates the data we are studying, the rational expectations formulation of Muth and Lucas opens the door to a comprehensive econometric approach. Consider an econometrician who does not know some or all of the parameters of the underlying economic model and who proceeds to infer those parameters using formal statistical methods that have come to be called rational expectations econometrics. To elaborate, let’s call probabilities that are model-consistent in the sense of Muth and Lucas ``model-implied probabilities’’. These probabilities can in principle be expressed as a function of the model’s parameters. The outcome is typically a set of cross-equation restrictions that link formally the beliefs of the economic agents within the model to the data generation. Computing these restrictions involves solving a set of nonlinear equations that include Euler equations like the asset pricing equation (7.19) above as well as other equations that help determine the complete Markov dynamics. Being able to compute these functions is what opens the door to the application of formal statistical methods such as maximum likelihood. Importantly, this approach assumes that at least one of the members of the parameterized set of statistical models is consistent with the data generating process and that it is this data generation that the economic agents within the model use in their decision making. An application of rational expectations econometrics thus relies heavily on the economist’s model being complete in the sense of [Geweke, 2010]. [Sargent, 1978], [Saracoglu and Sargent, 1978], [Sargent, 1979], [Hansen and Sargent, 1980], [Wallis, 1980], [Hansen and Sargent, 2019] and other contributions in [Lucas and Sargent, 1981] present early applications of this complete-specification approach. [Hansen and Sargent, 2013], ch. 9 describes time-domain and frequency domain maximum likelihood estimation for a class of linear-quadratic-Gaussian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models. These procedures are widely used throughout applied macro and monetary economics, due in part to the convenient software provided by [Adjemian et al., 2024] and [Herbst and Schorfheide, 2016].

[Hansen and Singleton, 1982] and [Hansen and Richard, 1987] suggest a different approach. They assume that an econometrician only has partial information and does not impose or fully parameterize the baseline probability model. Implicitly, they allow for the model components that are not fully parameterized to be revealed imperfectly (except in infinite sample limit) to the econometrician by the actual data generating process. Thus, [Hansen and Singleton, 1982] and [Hansen and Richard, 1987] replace Muth’s consistency axiom operational in a fully specified econometric model with another notion of consistency that is implied by a Law of Large Numbers limit in a statistical setting that assumes that process described by the baseline model is stationary and ergodic. Formally, this approach is implemented with a vector of conditional moment restrictions. [Hansen and Singleton, 1982] and [Hansen and Richard, 1987] thereby make possible a limited-information alternative to imposing rational-expectations with a fully-specified baseline model. Such an approach continues to adopt the simplification that economics agents, in contrast to an econometrician, know the underlying data generating process. Relieved of having to specify the full economic dynamic system, this limited information approach gains further flexibility by applying the law of iterated expectations to derive implications that the econometrician can use for estimation and testing. Applying such an approach in the context of the [Kazemi, 1992] setup converts the degenerate martingale restriction imposed by Kazemi into a moment restriction that accommodates estimation and statistical testing by using the generalized method of moments. See [Hansen, 1982].

There are now many published papers in the applied macro, industrial organization, and asset pricing literatures that apply either the ``rational expectations econometrics’’ approach that assumes that the econometrician knows a parameterized family models that includes the rational expectations equilibrium, while only the agents know the correct member of this parameterized family; or the alternative approach that assumes that the econometrician has only a partial a priori specification and that leverages the Law of Large Numbers implicitly to fill in the rest of the specification.

The rational expectations econometrics assumptions that a correctly-specified model is among the parameterized family and that the economic agents inside the model know key parameters that the econometrician does not are heroic, to put it politely. Even Lucas’s statement above expresses skepticism when he dismisses the statement that `People know the true structure of the world they live in’ as being silly. Sophisticated applied economists acknowledge up front that their models are approximations, meaning that they are misspecified. Instead of formally integrating their concerns about possible misspecifications into statistical implementations, for reasons of tractability users of rational expectations econometrics routinely ignore such approximation concerns. For skeptics, the rational expectations econometrics straitjacket is simply to too confining, leading them to adopt less formal methods of model matching and validation. Relatedly, without ever claiming or providing evidence that their model-implied expectations agree with an actual data generation process, many papers in applied theory routinely impose rational expectations in the process of constructing models of so-called stylized facts.

As we argued previously, a subjective belief specification is often expressible as a multiplicative martingale relative to a baseline probability specification, say the rational expectations counterpart or the probability that captures the actual data generation. Thus subjective beliefs offer one candidate for a multiplicative martingale component to the cumulative stochastic discount factor within the [Kazemi, 1992] setup. Statistical divergences provide a way to measure the magnitude of the belief-induced misspecification needed to capture empirical failures that arise from using one of the rational expectations econometrics approaches just described. This opens the door to using a statistical perspective to assess the role of subjective probabilities in models without rational expectations, in contrast to much of the existing research on subjective beliefs in asset pricing. See Section 7.9 for an elaboration. To it’s credit, rational expectations provides a framework for conducting counterfactuals using underlying dynamic economic model, along the lines of [Marschak, 1953] and [Hurwicz, 1966]. More general subjective belief formulations including ones represented by multiplicative martingales, unfortunately, struggle to do something comparable. Deciding when to use misspecified models and for what purposes are important challenges for applied researchers.

7.8. Values of stochastic cash flows#

In a fundamental paper, [Rubinstein, 1976] featured the importance of cash-flow pricing in contrast to the often studied return-based analyses.

7.8.1. Long-term risk-return tradeoff for cash flows#

Following [Hansen and Scheinkman, 2009] and [Hansen et al., 2008], we consider the valuation of stochastic cash flows, \(G\), that are multiplicative functionals. Such cash flows are determinants of prices of both equities and bonds.

We now study valuation from the perspective of the long-term limits measured by the logarithms of the eigenvalues, the \(\tilde \eta\)’s. long-term limits of prices of such cash flows. Consider a cash-flow growth process \(G\) measured as a multiplicative functional. The corresponding cash-flow return over horizon \(t\):

where we have normalized \(S_0 = 1\). Note that as a special case, the cash-flow return on a unit date \(t\) cash-flow is:

Define the proportional risk premium on the initial cash-flow return as the ratio of the expected return divided by the riskless counterpart for the same horizon. Taking logarithms and adjusting for the time horizon gives:

where in the first expression the first term is the logarithm of the expected payoff divided by, the second term is minus the logarithm of the price, and the third term is minus the logarithm of the riskless cash-flow return for horizon \(t\). Scaling by \(1/t\) adjusts for the investment horizon.

The product \(SG\) is itself a multiplicative functional. Let \(\eta^{sg}\) denote its geometric growth component. Then from (7.20), the limiting cash-flow risk compensation is:

under the moment restrictions imposed in limit (7.17). This expression resembles the negative of covariance as is often found in asset pricing, but it differs from a covariance because we are working with proportional measures of the risk compensations. When the cash flow process, \(G,\) is a cumulative return, the asset pricing restrictions informs us that \(SG\) is a martingale. Its this case, the proportional risk premium is just:

where, as we noted previously, \(- \eta_s\) is the long-term counterpart to a riskless rate of return.

7.8.2. Finite versus infinite-valued claims#

In a recent paper, [Panageas, 2025] reminds us that several important issues that bear on finite values of of claims to infinite cash flows, including macro processes like aggregate consumption and aggregate output. These issues include speculative bubbles, dynamic efficiency, and equity claims linked to macroeconomic outcomes. Importantly, he argues that the adjustment for uncertainty can play an important and sometimes subtle role in such evaluations.[1] We now explore in more detail when such valuations are finite taking account of uncertainty adjustments.

We start by building stochastic counterparts to the well known and pedagogically revealing Gordon growth model posed in discrete time. By using the framework developed in this chapter, we characterize the uncertainty adjustments necessary for such valuations. In so doing, we show how tools featured in Black-Scholes style option-pricing type analyses must be altered in important ways to understand these valuations.

We build a multiplicative functional using the product, \(M = G S,\) where \(G\) captures stochastic growth in the cash flow and \(S\) stochastic discounting. The factorization in Theorem 7.1 and the selection we featured in Theorem 7.2 provide a defense for using \(\tilde \eta\) as an asymptotic growth or decay rate of \(M\) provided that we select the solution that is stochastically stable. To justify finite values of equity-based assets for a family of cash flows, we restrict \(\tilde \eta<0\) so that stochastic discounting dominates stochastic growth. We now revisit that analysis, deconstruct the outcome, and explore the limitations.

7.8.2.1. Constant discounting#

As a warm-up, consider a discrete-time Gordon growth model where:

with \(\eta_s <0\) reflecting discounting and \(\eta_g\) capturing growth. The well known and simple to compute outcome gives:

for \(M = SG\), provided that \({\tilde \eta} = { \eta}_s + {\eta}_g < 0\). Thus we have the familiar restriction that discounting has to dominate growth in a deterministic setting.

As is also well-known, the separation is not quite so simple because growth contributes to the rate of return used for discounting. The term \({\tilde \eta}_s\) could reflect both subjective discounting in preferences and an adjustment contributed by economic growth in consumption that can either enhance or diminish the discount rate depending on investor preferences for intertemporal substitution.

7.8.2.2. Expected discounted cash flows#

Next consider discounted expected values for a \(\tilde \eta < 0 \) and a stochastically stable Markov process \(X\). Recall that stochastic stability implies that conditional expectations converge to their unconditional counterpart. Thus we, temporarily, abstract from uncertainty adjustments in valuation not reflected in conditional expectations or encoded in the discount rate. (We will be agnostic for how we come up with \(\tilde \eta\).) Consider the valuation of a positive claim on the Markov state say \(f(X),\)

Under the presumed stochastic stability of the Markov process, there are two possibilities are of interest:

While it is common to feature the finite-moment case, here we proceed more generally. Except for the finite-state Markov case, we may easily construct payoffs that are positive functions of the Markov state that have infinite expectations. When the unconditional expectation is infinite, the value of the equity-type claim may or may not be finite. In effect, there is a race between how fast the expectation diverges versus the magnitude of the discount rate \(- {\tilde \eta}\). When the former grows faster than \(- {\tilde \eta},\) the valuation in (7.21) will be infinite, even though the underlying Markov is stochastically stable.

Our more general approach required that we address a multiplicity that emerges when we factor \(M\). Take \(M_t =

\exp\left( \tilde \eta t \right) \phi(X_t).\) For sake of discussion, take \(S_t = \exp\left( \tilde \eta t\right)\), and \(G_t = \phi(X_t)\).

As a special case for such an \(M\) process, consider the solutions to the following equation:

Setting \({\hat e} = 1\) and \({\hat \eta} = 0\) solves this equation, but there can be other solutions. For such solutions, \( \hat \eta > 0,\) the conditional expectations will diverge geometrically, and they must have infinite unconditional moments. More generally, the potential divergence of the conditional moments is precisely the source of multiple factorizations for \(M,\) and what drives our choice of selecting one. The associated cash flow with a date \(t\) contribution, \(\phi(X_t) = {\hat e}(X_t),\) will have Infinite value when \(\hat \eta > - {\tilde \eta}\).

Example 7.9

Consider a special case of Example 7.8 with \(\nu = {\sf f}_1 = {\sf f}_2 =0. \) This makes \(M=1\). We look for solutions of the form:

The quadratic equation of interest simplifies to:

This has two solutions. One is \(\epsilon_2 = 0.\) For this one, \({\hat \eta}=0\) and \({\hat e} = 1\) and gives rise to the solution that we expect. For the other one,

\(\epsilon_1 = 0\), and

since \({\sf a}^2 < 1\).

7.8.2.3. A simple stochastic extension of the Gordon growth model#

To model stochastic growth and discounting, consider the very special case of two correlated geometric random walks with constant expected discounting or growth rates. Suppose

where \(\mu_s\) and \(\mu_g\) are constants with \(\mu_s < 0,\) \(\mu_g > 0\), and \(\sigma_s\) and \(\sigma_g\) are constant row vectors and the \(W\) process is iid with \(W_{t+1}\) being a multivariate standard normally distributed random vector. Form the product process, \(M = SG,\) which will have the same mathematical structure:

Construct

The first term in the second line captures the implied risk-free rate of the return, the second term the expected growth rate, and the third term, \(\sigma_s \cdot \sigma_g,\) includes an adjustment for uncertainty. The security with cash flow \(G\) has finite value when \(\tilde \eta < 0\) with the familiar geometric summation formula:

This computation illustrates a way to build a stochastic version the Gordon growth model, but it has important limitations from both a conceptual and empirical perspective.

7.8.2.4. Adjusting for uncertainty II#

The stochastic example in the previous subsection has pedagogical value, but the interest rates are constant as are the cash-flow growth rates. The same is true for the one-period cash-flow exposures to the shock vector \(W_{t+1}\). We escape this straight jacket by introducing state dependence expressed as follows:

By using the factorization of Theorem 7.1 and the unique Theorem 7.2 selection of such a representation, we return to our initial present-value analysis in [Subsection 7.8.1.2]:Expected discounted cash flows. Write

where \(M = SG\). Consider a family of cash flows of the form

for different choices of \( f = {\tilde f } {\tilde e} \) and \(\tilde f \in {\mathcal F}(\widetilde L))\) given by (7.16). Stated in terms of logarithms, the cash-flows are all co-integrated (with co-integration coefficients one and minus one). The process \(G\) reflects a common stochastic growth component. [Hansen, 2012] explores in detail relations between co-integration as it is studied in macroeconomics and long-term valuation as it is of interest in this chapter. In particular, the set \({\mathcal F}(\widetilde L)\) imposes moment restriction for the valuation limits. Distinct moment implications are made other applications of co-inetgration.

The uncertainty-adjusted valuation of the discounted cash flows of the form given in (7.23) is given by:

where the expectation uses the probability distribution induced by \({\widetilde E}\). Analogous to our initial computation, if \(\tilde \eta < 0,\) the valuation will be finite. Infinite values will arise whenever \({\tilde \eta} \ge 0.\) Thus, \({\tilde \eta}\) as a measure of the asymptotic growth or decay in \(SG,\) plays a central role in determining whether the discounted expected value of the cash-flow \(G\) is finite or not. But like the analysis in [Subsection 7.8.1.2]:Expected discounted cash flows, there is a nuanced case in which

For this infinite-moment case, whether the discounted expected value is finite or not, depends on the rate of divergence in comparison to \(- {\tilde \eta}\).

Importantly, this analysis uses a change in probability measure for the computation. The change of measure mathematically resembles a standard risk-neutral probability, but it is conceptually distinct. It depends on the stochastic behavior of \(SG\) and not just \(S\). Moreover, state-dependent short-term interest rates alone make the risk-neutral probabilities not the relevant one for valuing long-term cash flows. With state-dependence in stochastic growth, it becomes valuable to move from \(S\) to \(SG,\) which builds on the Gordon-growth insight. The uncertainty adjustments for valuation depend on the implied asymptotic rate of growth or decay, \(-{\tilde \eta},\) analogous to what happens in deterministic environments. It could, however, also depend on the corresponding behavior of the conditional expectations,

of the cash flows as the payoff horizon becomes large.

Although stated in the context of a very special example, the analysis in [Panageas, 2025] reminds us that in a stochastic setting, unconditional moments can be infinite even when there is stochastic stability in the Markov process and the horizon-dependent conditional moments are finite. This means the value comparison for stochastic cash-flows with different specifications of \(f\) could be dramatically different because of the tail behavior of the stationary distributions of random variables \(f(X_t)/{\tilde e}(X_t)\) for the different \(f\)’s. More than the rate \({\tilde \eta}\) may come into play. It would appear to be hard to tell how restrictive the finite moment condition is empirically, but that does not mean we should dismiss it as a possibility. It sometimes matters when we build explicit models of valuation as illustrated by [Panageas, 2025].

7.8.3. Partitioning long-term return implications#

We study a family of cash-flow and holding period returns where the cash flows are of the form (7.23) under some moment restrictions on \(f(X_t)\). Specifically, we study limiting returns as the payoff horizon becomes long are the same for alternative choices of \(f > 0.\) [Jiang et al., 2024] use valuation impact of cointegration in the relation between government spending and revenue to assess the implied value of government debt in comparison to actual direct measurements.

7.8.3.1. Cash-flow returns#

Consider two factorizations:

Given \(G\), entertain a family of cash flows that can be represented as in (7.23) for \(f>0\)’s such that

The two factorizations of interest for cash flows (7.23) are:

Implicit in these factorizations that the introduction of \(f\), and no impact on the Perron-Frobenius eigenvalues nor does it alter the multiplicative martingales. It does change the eigenfunction by replacing \(e^g\) with \(e^g/f\). With these extensions along wtth moment restrictions (7.24), the limiting expected growth and valuation rates are:

Observe that the limits remain the same for alternative choices of \(f>0\) as is the expected rate of return given by:

7.8.3.2. One-period holding-period returns#

We also investigate the limiting behavior of one-period holding-period returns and obtain an even stronger connection among the family of returns for cash flows satisfying To achieve this, we revisit and extend a computation we performed previously. Consider the multiplicative factorization again and pricing future cash flows in single periods. (These are sometimes referred to as “strips.”) An empirical asset pricing literature has explored these returns starting with [van Binsbergen et al., 2012]. See [Golez and Jackwerth, 2024] for a recent update of this evidence.

The one-period holding period return on a \(t\)-period asset with payout \(G_tf(X_t)\) at date \(t\) is:

where the \(\tilde \cdot\) conditional expectation uses the probability measure induced by the positive martingale \(L^{sg}\). Using stochastic stability and taking limits as \(t\) tends to \(\infty\) gives the limiting holding-period return:

provided that \(f/e^{sg} \in {\mathcal F}(L^{sg})\). The limiting holding-period return does not depend on \(f\).

Much of this this chapter has featured factorizations that allow us to deconstruct economically interesting processes including growth processes. We now consider a way to parametrize cash-flow growth processes in terms of holding period returns and decay rates. We do this to reveal common long-term risk exposures positive cash-flow growth processes . Formally, we build partitions of such processes. For a given a cumulative stochastic discount factor process \(S\) with \(S_0=1,\) parameterize a baseline stochastic cash flows as

where

\(\eta\) is a positive decay rate \(\eta\);

\(R\) is a one-period return process constructed as

for some \(\kappa\);

the implied multiplicative martingale with increment

and \(L_0 = 1\) induces a stochastically stable process for \(X\).

Notice that for a given cumulative stochastic discount factor process \(L\) reveals \(R\) and conversely. Since we restrict \(R\) via its impliications for the martingale \(L\), we use the notation \(G(\eta,L)\) to denote the baseline process by \(G(\eta, L)\). The initial condition \(G_0(\eta, L) > 0\) is inconsequential at this juncture.

For each baseline process, introduce a family of cash-flow growth processes within a partition:

Notice that for each \(G\) in a partition \({\mathcal G}(\eta, L),\) we have the factorization:

for some \(f \in {\mathcal F}(L).\) Each such member has the same one-period holding period return, \(R\).

For a given cash-flow process, \(G\), reveal the corresponding \((\eta, L)\) and the relevant partition to which \(G\) belongs. Consider two cash flow processes \(G^1\) and \(G^2\) within the universe of all of the partitions that are related by:

Thus they are co-integrated in logarithms with vector \((1, -1)\). These processes are necessary within the same partition with a common \((\eta, L)\).

Remark 7.10

[Ai and Fu, 2025] extend the holding-return limits derived here to study what can be revealed by announcement impacts on financial markets. They use a continuous-time formulation with hidden states and preset announcement dates at which information is revealed about monetary policy. They study instantaneous returns at the times of the announcements. They deduce counterpart representations applicable to such holding-period returns. They use this setup to estimate long-term impacts of money policy announcements on the macro economy as revealed by such returns. Their analysis is facilitated by their use of log-linear models with Brownian motion increments, which opens the door to a tractable link between the multiplicative martingale increments and permanent shocks revealed by additive decompositions applied to logarithms.

7.9. Bounding investor beliefs#

We use the cumulative stochastic discount factorization to analyze two distance approaches to drawing inferences about investor beliefs.

7.9.1. Subjective beliefs in the absence of long-term risk#

Suppose that we have data on prices of one-period state-contingent claims. We can use these data to infer the one-period operator, \({\mathbb M}.\) Recall that we represent this operator using a baseline specification of the one-period transition probabilities. One possibility is that the one-period baseline transition probabilities agree with the data generation. Rational expectations models equate transition probabilities to those used by investors. More generally, investors could have subjective beliefs that can differ from the baseline specification:

investors think there are no permanent macroeconomic shocks;

investors don’t have risk-based preferences that can induce a multiplicative martingale in a cumulative stochastic discount factor process.[2]

Under these two restrictions, we could identify the \(L^s\) as the likelihood ratio for investor beliefs relative to the baseline probability distribution. Thus, the implied martingale component in the cumulative stochastic discount factor identifies the subjective beliefs of investors. Using this change of measure, the limiting long-term risk compensations derived in the previous section are zero. These assumptions facilitate “Ross recovery” of investor beliefs.[3]

7.9.2. Restricting the martingale increment with limited asset market data#

Initially, suppose we impose rational expectations by endowing investors with knowledge of the data generating process. With limited asset market data we cannot identify the martingale component to cumulative stochastic discount factor process without additional model restrictions. We can, however, obtain potentially useful bounds on the martingale increment. For some applications, in addition to those of [Alvarez and Jermann, 2005], [Bakshi and Chabi-Yo, 2012], see [Koijen et al., 2010]and [Lustig et al., 2019], among others. We know that the implied martingale has some peculiar limiting behavior and that martingale and transient components can be correlated. Nevertheless, the implied probability measure can be well behaved. Consequently, in contrast to the references just cited, we use the increment as a device to represent conditional probabilities instead of just as a random variable. Extensions of these same methods can be used to study restrictions on subjective beliefs implied by asset prices.

There is a substantial literature on divergence measures for probability densities. Relative entropy is an important example. More generally, consider a convex function \(\phi\) that is zero when evaluated at one. Jensen’s inequality implies that

and equal to zero when \(N_1\) is one, provided that \(N_1\) is a multiplicative martingale increment (has conditional expectation one). This gives rise to a family of \(\phi\) divergences that can be used to assess departures from baseline probabilities. Relative entropy, \(\phi(n) = n \log n\) is an example that is particularly tractable and has been used often. Both \(n \log n\) and \(- \log n\) can be interpreted as expected log-likelihood ratios.

One way of assessing the magnitude of the martingale increment to the stochastic discount factor is to solve:

Minimum divergence Problem

subject to:

where \(Y_1\) is a vector of asset payoffs and \(Q_0\) is a vector of corresponding prices, and where \({\widehat S_1}/{\widehat S_0}\) is equal to one of the two possibilities:

i) \(\exp(\eta^s) \frac{ e^s(X_0)} {e^s(X_1)}\) under under the data generating process;

or

ii) an imposed stochastic discount factor allowing for subjective beliefs to differ from the data generating process.

In regards to i), recall that the term

can be approximated by the reciprocal of the one-period holding-period return on a long-term bond. In regards to ii), for a model that is misspecified under the data generating process, we can ask that the distortion induced by the subjective beliefs correct the misspecification under the data generating process.

Remark 7.11

It is enlightening to extend problem (7.26) to include an inequality constraint requiring that the conditional expectation of any random variable of interest be less than or equal to some threshold. Adding a constraint, when it binds, increases the objective. A given increase in the divergence is achieved by reducing this threshold sufficiently far. By following this procedure, we can find a lower bound on the moment of interest that increases the objective by some pre-specified percentage. Extending this approach to any bounded random variable reveals an ambiguity-induced nonlinear expectation operator, where the nonlinearity follows from our construction of a lower bounds on conditional expectations. To obtain an ambiguity interval for a given random variable follows from also constructing the lower bound for the negative of this random variable. See [Chen et al., 2020] for a more extensive discussion. Such a constructions are an example of what econometricians describe as partial identification because the vector \(Y_1\) of asset payoffs used in the analysis may not be sufficient to reconstruct all potential one-period asset payoffs and prices. In effect, the econometrician is often confronted with incomplete data on financial markets.

Remark 7.12

Many researchers use \(\phi(n) = - \log n\) as a divergence measure. [Chauduri et al., 2023] and [Chen et al., 2024], however, isolate a potentially problematic aspect of monotone decreasing divergences such as \(- \log n\) because they can fail to detect certain limiting forms of deviations from baseline probabilities.

Remark 7.13

[Ghosh and Roussellet, 2023] suggest a formal econometric procedure for estimating the minimum divergence altered probability measure using conditioning information. Presumably their methods could be extended to produce conditional ambiguity intervals as well.

Remark 7.14

To avoid having to estimate conditional expectations, applications often study unconditional expectations. In such situations, conditioning can be brought in through the “back door” by scaling payoffs and prices with variables in the conditioning information set; for example, see [Hansen and Singleton, 1982] and [Hansen and Richard, 1987]. See [Bakshi and Chabi-Yo, 2012] and [Bakshi et al., 2017] for some related implementations.

Remark 7.15

[Alvarez and Jermann, 2005] use \(- {\mathbb E}\left( \log S_1 + \log S_0 \right) \) as the objective to be minimized. Notice that

where the term in square brackets is the logarithm of the reciprocal of the limiting holding-period bond return. The criterion thus equals that in the minimum divergence problem, but with an additive translation. Rewrite the constraints in the minimum divergence problem as:

This leaves us with an equivalent minimization problem in which the translation term is subtracted off to obtain the bound of interest.

Applied researchers have sometimes omitted the first constraint, which weakens the bound.

7.9.2.1. Intertemporal divergence measures#

[Chen et al., 2020] propose extensions of the one-period divergence measures to multi-period counterparts that remain tractable and enlightening. By looking over time, the dynamic formulation essentially averages over the conditioning information; but it allows for subjectivity in the transition probabilities. Their dynamic measure of divergence is constructed as follows. For a given \(N\) process, let

As we have seen, this construction provides the implied transition probability adjustments for the alternative time horizons. Find a function \(\psi\) such that

With these inputs form an alternative equivalent way to represent the one-period divergence by constructing a function \(\psi\) such that

The function \(\psi\) plays a role analogous to \(\phi\) when the roles between the \(N\)-implied probability and the baseline probability are interchanged. It may be shown that \(\psi\) also strictly convex. Note also that \(\psi(1) = \phi(1) = 1\). By design,

With these building blocks, [Chen et al., 2020] suggest the divergence measure:

An alternative equivalent representation may be obtained by taking a Law of Large Numbers limit under the altered probability measure. When \(\phi(n) = n \log n,\) this divergence measure coincides with the one that is pertinent for the study of Donsker-Varadhan formulations of large deviations in Markov environments. This dynamic formulation of divergences opens the door to recursions for the bounds in the divergence minimization described in Remark 7.11.

7.9.2.2. Subjective belief bounds on proportional risk premia#

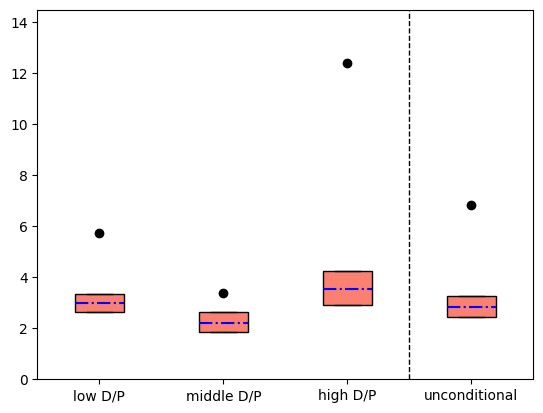

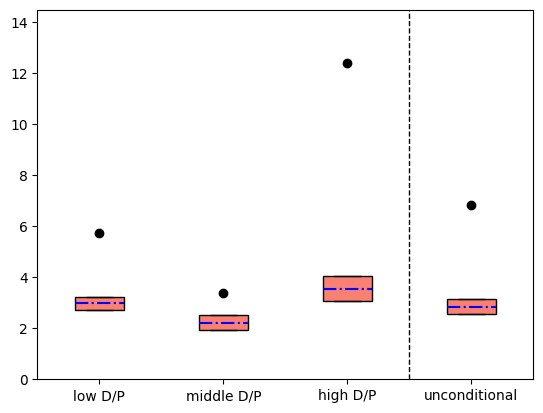

The next two figures report proportional risk compensations for the market return using an illustration from [Chen et al., 2020] under a presumed data generation and when distorted investor beliefs are permitted and risk aversion is constrained to be one. The compensations condition on dividend/price ratios. The figures includes upper and lower endpoints of conditional expectations computed by extending the divergence minimization problem along the lines suggested Remark 7.11 given by the upper and lower edges of shaded rectangles. The horizontal lines within the shaded rectangles given the conditional moments implied by the minimum divergence change in probability measure. By comparing the two figures, we see how ambiguity intervals decrease when we weaken the constraint on the divergence. Since the divergence measure used in the computation is explicitly dynamic, the associated subjective probabilities for the transition probabilities are also substantially altered. The implied stationary probabilities for the three states are

Notice that the altered probabilities reflect a substantial reduction of being in the high dividend-price state, making the big conditional divergence for the high dividend-price state seem to have a smaller effect on the dynamic divergence measure.

Fig. 7.3 Proportional risk compensations computed as \(\log \mathbb{E} R^m - \log \mathbb{E} R^f\) scaled to annualized percentages. The \(\bullet\)s are the empirical averages and the boxes give the imputed bounds when we inflated the minimum relative entropy by 20%.#

Fig. 7.4 Proportional risk compensations computed as \(\log \mathbb{E} R^m - \log \mathbb{E} R^f\) scaled to an annualized percentage. The \(\bullet\)s are the empirical averages and the boxes give the imputed bounds when we inflated the minimum relative entropy by 10%.#

7.9.2.3. Subjective belief factor#

[Cui et al., 2025] use a complementary approach to study subjective beliefs and asset prices. They use a convenient mathematical representation of linear functionals. Consistent with our previous discussion, distorted expectations are viewed as a (conditional) linear mapping from the random variables being forecast to associated conditional predictions. A belief factor is identified as the random variable that appears in this representation of a conditional linear functional in a mathematical formulation in [Hansen and Richard, 1987] and [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2016]. [Cui et al., 2025] use this belief factor to organize useful descriptions of a various data sets containing reports of subjective beliefs. In this setting, the subjective belief factor is restricted to be a (conditional) linear combination of the variables being forecast in the data set of interest, a restriction central to econometric identification. As [Cui et al., 2025] point out, extending the subjective belief functional to include forecasts of other variables omitted from a data set under study generates subjective belief factors whose best linear (conditional) predictors equal the subjective belief factor that they construct from their smaller data set. While identification remains partial in this, their framework has provides convenient characterizations of what can be learned and why it is informative.

[Cui et al., 2025] correctly remind us that they do not restrict the subjective belief factor to be positive. They go on to suggest a way to impose positivity under some particular distributional assumptions. As we have seen, by using statistical divergences, the [Chen et al., 2020] analysis avoids these auxiliary assumptions while still imposing positivity. It also provides an entirely different characterization of partial identification than does the approach of [Cui et al., 2025]. There are advantages and disadvantages to both approaches.