11. Risk, Ambiguity, and Misspecification[1]#

Pioneers in Uncertainty and Decision Theory. Frank Knight, Abraham Wald, abd Jimmie Savage.

“Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of risk, from which it has never been properly separated…. and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomena depending on which of the two is really present and operating.” [Knight, 1921]

11.1. Introduction#

Likelihood functions are probability distributions conditioned on parameters; prior probability distributions describe a decision maker’s subjective belief about those parameters.[2] By distinguishing roles played by likelihood functions and subjective priors over their parameters, this chapter brings some recent contributions to decision theory into contact with statistics and econometrics in ways that can address practical econometric concerns about model misspecifications and choices of prior probabilities.

We combine ideas from control theories that construct decision rules that are robust to a class of model misspecifications with axiomatic decision theories invented by economic theorists. Such decision theories originated with axiomatic formulations by von Neumann and Morgenstern, Savage, and Wald ([Wald, 1947, Wald, 1949, Wald, 1950], [Savage, 1954]). Ellsberg ([Ellsberg, 1961]) pointed out that Savage’s framework seems to include nothing that could be called “uncertainty” as distinct from “risk”. Theorists after Ellsberg constructed coherent systems of axioms that embrace a notion of ambiguity aversion. However, most recent axiomatic formulations of decision making under uncertainty in economics are not cast explicitly in terms of likelihood functions and prior distributions over parameters.

This chapter reinterprets objects that appear in some of those axiomatic foundations of decision theories in ways useful to an econometrician. We do this by showing how to use an axiomatic structure to express ambiguity about a prior over a family of statistical models, on the one hand, along with concerns about misspecifications of those models, on the other hand.

Although they proceeded differently than we do here, [Chamberlain, 2020], [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2013], and [Denti and Pomatto, 2022] studied related issues. [Chamberlain, 2020] emphasized that likelihoods and priors are both vulnerable to potential misspecifications. He focused on uncertainty about predictive distributions constructed by integrating likelihoods with respect to priors. In contrast to Chamberlain, we formulate a decision theory that distinguishes uncertainties about priors from uncertainties about likelihoods. [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2013] (section 4.2) provided a rationalization of the smooth ambiguity preferences proposed by [Klibanoff et al., 2005] that includes likelihoods and priors as components. [Denti and Pomatto, 2022] extended this approach by using an axiomatic revealed preference approach to deduce a parameterization of a likelihood function. However, neither [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2013] nor [Denti and Pomatto, 2022] sharply distinguished prior uncertainty from concerns about misspecifications of likelihood functions. We want to do that. We formulate concerns about statistical model misspecifications as uncertainty about likelihoods.

More specifically, we align definitions of statistical models, uncertainty, and ambiguity with ideas from decision theories that build on [Anscombe and Aumann, 1963]’s way of representing subjective and objective uncertainties. In particular, we connect our analysis to econometrics and robust control theory by using Anscombe-Aumann states as parameters that index alternative statistical models of random variables that affect outcomes that a decision maker cares about. By modifying aspects of [Gilboa et al., 2010], [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2013], and [Denti and Pomatto, 2022], we show how to use variational preferences to represent uncertainty about priors and also concerns about statistical model misspecifications.

Discrepancies between two probability distributions occur throughout our analysis. This fact opens possible connections between our framework and some models in “behavioral” economics and finance that assume that decision makers inside their models have expected utility preferences in which an agent’s subjective probability – typically a predictive density – differs systematically from the predictive density that the model user assumes governs the data.[3] Other “behavioral” models focus on putative differences among agents’ degrees of confidence in their views of the world. Our framework implies that the form taken by a “lack of confidence” should depend on the probabilistic concept about which a decision maker is uncertain. Preference structures that we describe in this chapter allow us to formalize different amounts of “confidence” about details of specifications of particular statistical models, on one hand, and about subjective probabilities to attach to alternative statistical models, on the other hand. Our representations of preferences provide ways to characterize degrees of confidence in terms of statistical discrepancies between alternative probability distributions.[4]

11.2. Background motivation#

We are sometimes told that we live in a “data rich” environment. Nevertheless, data are often not “rich” along all of the dimensions that we care about for decision making. Furthermore, data don’t “speak for themselves”. To get them to say something, we have to posit a statistical model. For all the hype, the types of statistical learning we actually do is infer parameters of a family of statistical models. Doubts about what existing evidence has taught them about some important dimensions has led some scientists to think about what they call “deep uncertainties.” For example, in a recent paper we read:

“The economic consequences of many of the complex risks associated with climate change cannot, however, currently be quantified. … these unquantified, poorly understood and often deeply uncertain risks can and should be included in economic evaluations and decision-making processes.” [Rising et al., 2022]

In this chapter, we formulate “deep uncertainties” as lack of confidence in how we represent probabilities of events and outcomes that are pertinent for designing tax, benefit, and regulatory policies. We do this by confessing ambiguities about probabilities, though necessarily in a restrained way.

In our experience as macroeconomists, model uncertainties are not taken seriously enough, too often being dismissed as being of “second-order”, whatever that means in various contexts. In policy-making settings, there is a sometimes misplaced wisdom that acknowledging uncertainty should tilt decisions toward passivity. But in other times and places, one senses that the model uncertainty emboldens pretense:

“Even if true scientists should recognize the limits of studying human behavior, as long as the public has expectations, there will be people who pretend or believe that they can do more to meet popular demand than what is really in their power.” [Hayek, 1989]

As economists, part of our job is to delineate tradeoffs. Explicit incorporation of precise notions of uncertainty allows us to explore two tradeoffs pertinent to decision making. Difficult tradeoffs emerge when we consider implications from multiple statistical models and alternative parameter configurations. Thus, when making decisions, how much weight should we assign to best “guesses” in the face of our model specification doubts, versus possibly bad outcomes that our doubts unleash? Focusing exclusively on best guesses can lead us naively to ignore adverse possibilities worth considering. Focusing exclusively on worrisome bad outcomes can lead to extreme policies that perform poorly in more normal outcomes. Such considerations induce us to formalize tradeoffs in terms of explicit expressions of aversions to uncertainty.

There are also intertemporal tradeoffs: should we act now, or should we wait until we have learned more? While waiting is tempting, it can also be so much more costly that it becomes prudent to take at least some actions now even though we anticipate knowing more later.

11.2.1. Aims#

In this chapter we allow for uncertainties that include

risks: unknown outcomes with known probabilities;

ambiguities: unknown weights to assign to alternative probability models;

misspecifications: unknown ways in which a model provides flawed probabilities;

We will focus on formulations that are tractable and enlightening.

11.3. Decision theory overview#

Decision theory under uncertainty provides alternative axiomatic formulations of “rationality.” As there are multiple axiomatic formulations of decision making under uncertainty, it is perhaps best to replace the term “rational” with “prudent.” While these axiomatic formulations are of intellectual and substantive interest, in this chapter we will focus on the implied representations. This approach remains interesting because we have sympathy for Savage’s own perspective on his elegant axiomatic formulation:

Indeed the axioms have served their only function in justifying the existential parts of Theorems 1 and 3; in further exploitation of the theory, …, the axioms themselves can end, in my experience, and should be forgotten.” [Savage, 1952]

11.3.1. Approach#

In this chapter we will exploit modifications of Savage-style axiomatic formulations from decision theory under uncertainty, to investigate notions of uncertainty beyond risk. The overall aim is to make contact with applied challenges in economics and other disciplines. We will start with the basics of statistical decision theory and then proceed to explore extensions that distinguish concerns about potential misspecifications of likelihoods from concerns about the misspecification of priors. This opens the door to better ways for conducting uncertainty quantification for dynamic, stochastic economic models used for private sector planning and governmental policy assessment. It is achieved by providing tractable and revealing methods for exploring sensitivity to subjective uncertainties, including potential model misspecification and ambiguity across models. This will allow us to systematically:

assess the impact of uncertainty on prudent decision or policy outcomes;

isolate the forms of uncertainty that are most consequential for these outcomes.

To make the methods tractable and revealing we will utilize tools from probability and statistics to limit the type and amount of uncertainty that is entertained. As inputs, the resulting representations of objectives for decision making will require a specification of aversion to or dislike of uncertainty about probabilities over future events.

11.3.2. Anscombe-Aumann (AA)#

[Anscombe and Aumann, 1963] provided a different way to justify Savage’s representation of decision making in the presence of subjective uncertainty. They feature prominently the distinction between a “horse race” and a “roulette wheel”. They rationalize preferences over acts, where an act maps states into lotteries over prizes. The latter is the counterpart to a roulette wheel. Probability assignments over states then become the subjective input and the counterpart to the “horse race.”

[Anscombe and Aumann, 1963] used this formulation to extend the von Neumann-Morgenstern expected utility with known probabilities to decisions problems where subjective probabilities also play a central role as in Savage’s approach. While [Anscombe and Aumann, 1963] provides an alternative derivation of subjective expected utility, many subsequent contributions used the Anscombe-Aumann framework to extend the analysis to incorporate forms of ambiguity aversion. Prominent examples include [Gilboa and Schmeidler, 1989] and [Maccheroni et al., 2006]. In what follows we provide a statistical slant to such analyses.

11.3.3. Basic setup#

Consider a parameterized model of a random vector with realization

where

Denote by

Since the decision rule can depend on

The preferences over prize rules imply a ranking over decision rules, the

Risk is assessed using expected utility with a utility function

Following a language from statistical decision theory, we call

We allow the utility function to depend on the unknown parameter

11.3.4. A simple statistical application#

As an illustration, we consider a model selection problem. Suppose

The decision rule,

We allow for intermediate values between zero and one, which can be interpreted as randomization. These intermediate choices will end up not being of particular interest for this example.

The utility function for assessing risk is:

where

A class of decision rules, called threshold rules, will be of particular interest. Partition

where the intersection of

For a threshold rule, the conditional expected utility is

Suppose that the utility weights

11.4. Subjective expected utility#

Order preferences over

for a specific

We use these preference for a decision problem where prize rules are restricted to be in the set

Problem 11.1

Recall that partitioning of

These factorizations in (11.2) allow us to write the objective as:

To solve problem (11.1), it is convenient to exchange the orders of integration in the objective:

Notice that even if the utility function

As

for each value of

for given constraint sets

Problem 11.2

Finally, notice that

is the Bayesian posterior distribution for

Problem 11.3

since in forming the objective of conditional problem, (11.5), we divided the objective for the conditional problem, (11.4) by a function of

For illustration purposes, consider the example given in Section A simple statistical application. In this example,

Consider the conditional problem. If the decision maker chooses model one, then the conditional expected utility is

and chooses a model in accordance to this maximization. This maximization is equivalent to

expressed in terms of the prior, likelihood, and utility contributions. Taking logarithms and rearranging, we see that model

If the right side of this inequality is zero, say because prior probabilities are the same across models and utility weights are also the same, then the decision rule says to maximize the log likelihood. More generally, both prior weights and utility weights come into play.

Notice that this decision rule is a threshold rule where we use the

posterior probabilities to partition the

The Bayesian solution to the decision problem is posed assuming full confidence in a subjective prior distribution. In many problems, including ones with multiple sources of uncertainty, such confidence may well not be warranted. Such a concern might well have been the motivation behind Savage’s remark:

… if I knew of any good way to make a mathematical model of these phenomena [vagueness and indecision], I would adopt it, but I despair of finding one. One of the consequences of vagueness is that we are able to elicit precise probabilities by self-interrogation in some situations but not in others.

Personal communication from L. J. Savage to Karl Popper in 1957

11.5. An extreme response#

Suppose we go to the other extreme and avoid imposing a prior altogether. Compare two prize rules,

11.5.1. Constructing admissible decision rules#

One way to construct an admissible decision rule is to impose a prior and solve the resulting Bayesian decision problem. We give two situations in which this result necessarily applies, but there are other settings where this result is known to hold.

Proposition 11.1

If an ex ante Bayesian decision problem, (11.1), has a unique solution (except possibly on a set that has measure zero under

Proof. Let

for all

Proposition 11.2

Suppose

Proof. Let

for

But this latter inequality must hold with equality. Since each element of

Remark 11.1

While we are primarily interested in the use of alternative subjective priors as a way to construct admissible decision rules, sufficient conditions have been derived under which we can find priors that give Bayesian justifications for all admissible decision rules. Such results come under the heading of Complete class theorems. See, for instance, [LeCam, 1955], [Ferguson, 1967], and [Brown, 1981].

11.5.2. A simple statistical application reconsidered#

For illustration purposes, we again consider the model selection example. Consider a threshold decision rule of the form:

From formula (11.6), provided that we choose the prior probabilities to satisfy:

threshold rule (11.8) solves a Bayesian decision problem. Thus the implicit prior for the threshold rule is:

To provide a complementary analysis, form:

and use the probability measure for

This follows from the construction of

where we include the multiplication by

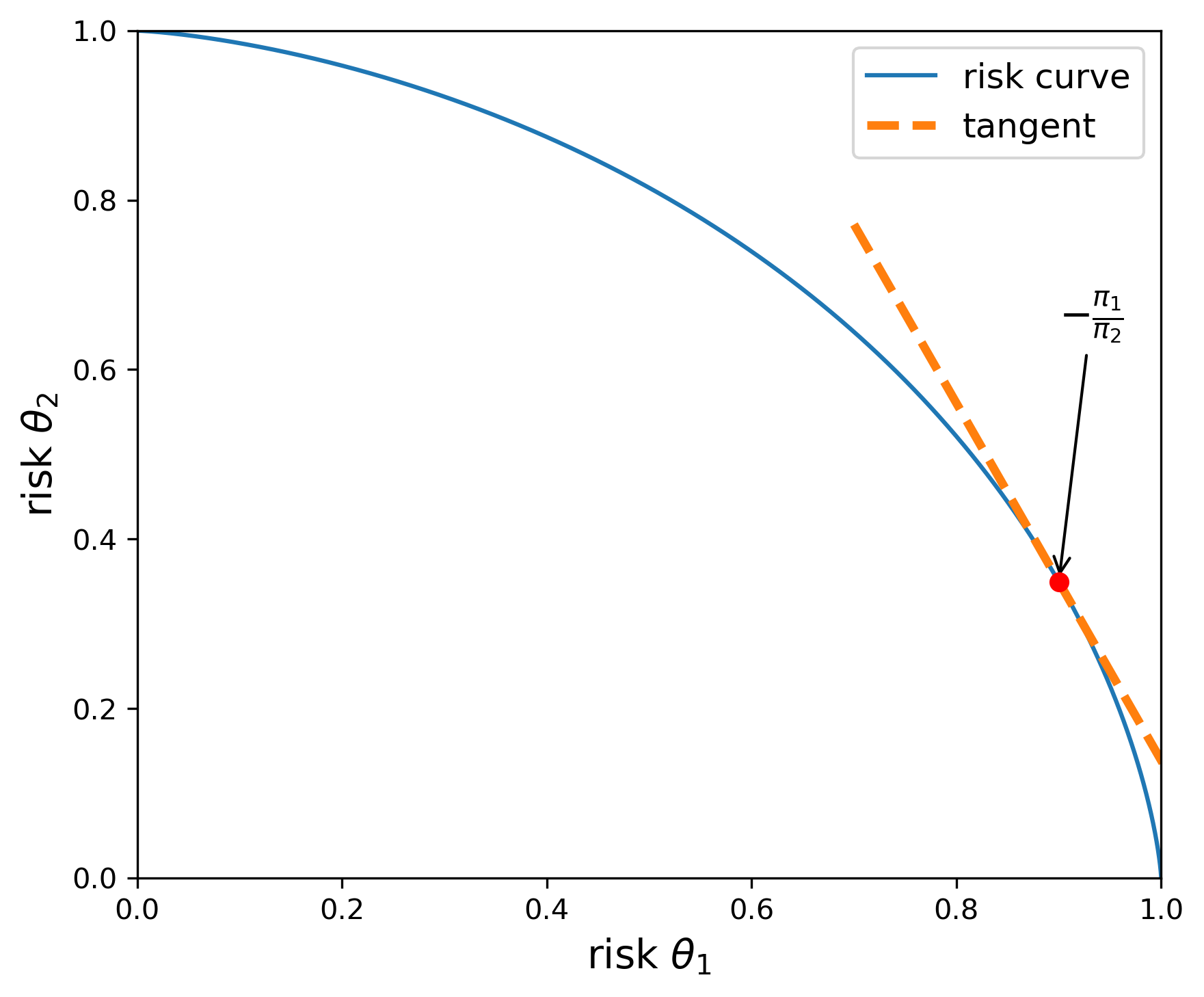

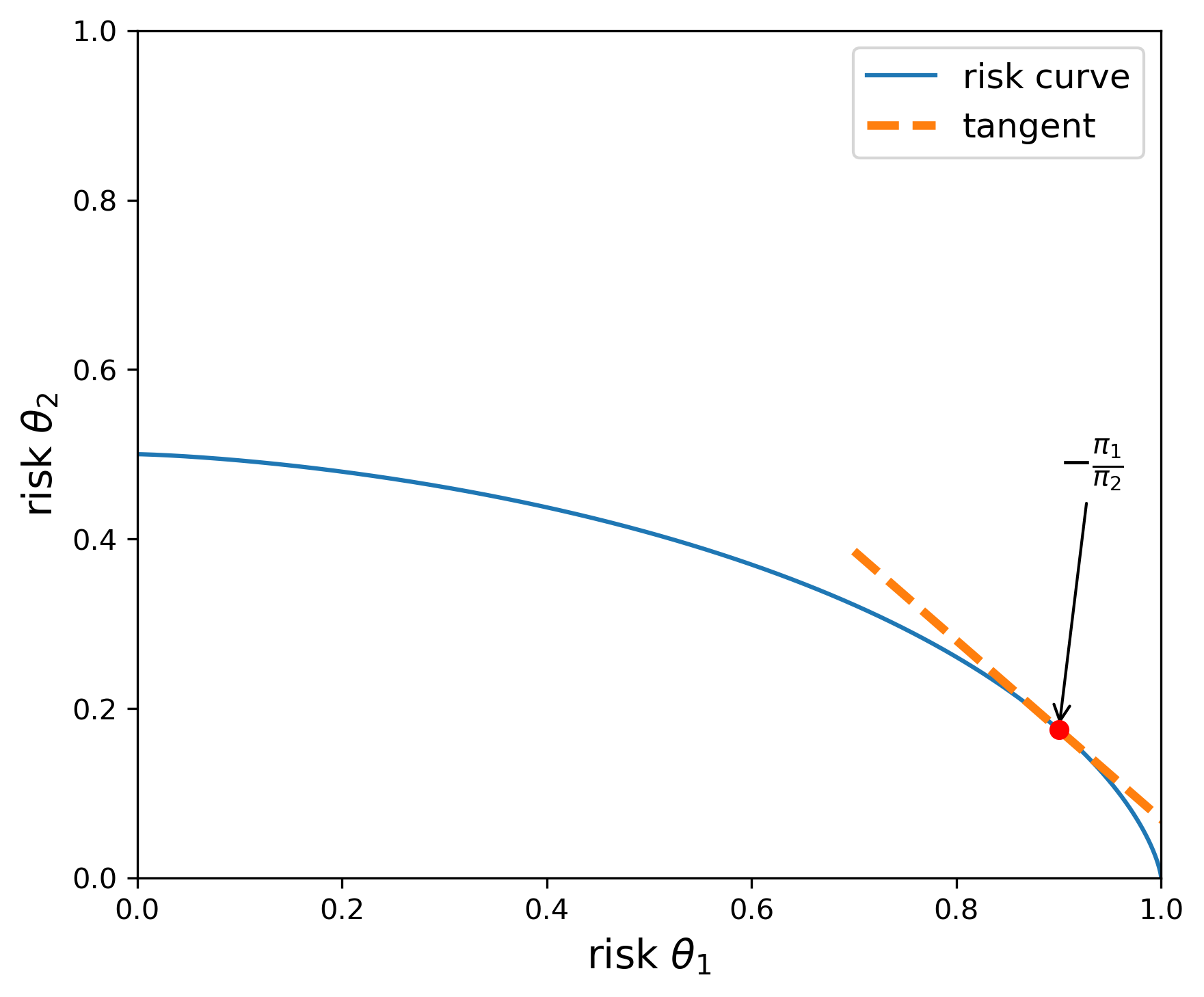

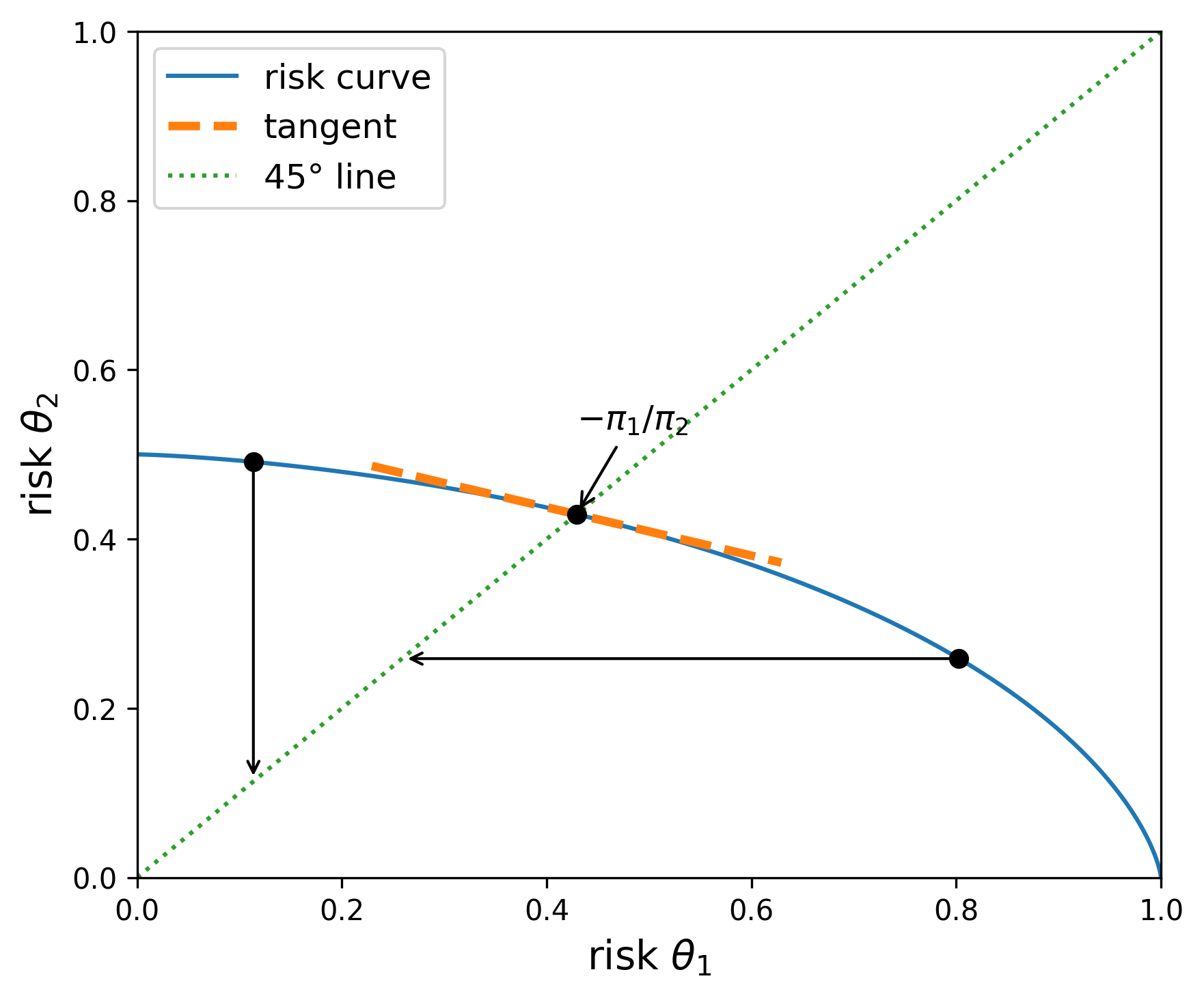

Consider the two-dimensional curve of model risks,

We compute the second-order derivative of the curve as

and hence the curve is concave.

Using prior probabilities to weight the two risks gives:

Maximizing this objective by choice of a threshold

implying that

As expected, this agrees with (11.9). Thus the negative of the slope of the curve reveals the ratio of probabilities that would justify a Bayesian solution given a threshold

We illustrate this computation in Figures Fig. 11.1 and Fig. 11.2. Both figures report the upper boundary of the set of feasible risks for alternative decision rules. The risks along the boundary are attainable with admissible decision rules. The utility weights,

Fig. 11.1 The blue curve gives the upper boundary of the feasible set of risks. The utility function parameters are given by

Fig. 11.2 The blue curve gives the upper boundary of the feasible set of risks. The utility function parameters are given by

11.6. Divergences#

To investigate prior sensitivity, we seek a convenient way to represent a family of alternative priors. We start with a baseline prior

Call this collection

Introduce a convex function

Of course, many such divergences could be built. Three interesting ones use the convex functions:

The divergence implied from the third choice is commonly used in applied probability theory and information theory. It is called Kullback-Leibler divergence or relative entropy.

11.7. Robust Bayesian preferences and ambiguity aversion#

Since the Bayesian ranking of prize rules depends on the prior distribution, we now explore how to proceed if the decision maker does not have full confidence in a specific prior. This leads naturally to an investigation of prior sensitivity. A decision or policy problem provides us with an answer to the question: sensitive to what. One way to investigate prior sensitivity is to approach it from the perspective of robustness. A robust decision rule then becomes one that performs well under alternative priors of interest. To obtain robustness guarantees, we are naturally led to minimization, providing us with a lower bound on performance. As we will see, prior robustness has very close ties to preferences that display ambiguity aversion. Just as risk aversion induces a form of caution in the presence of uncertain outcomes, ambiguity aversion induces a caution because of the lack of confidence in a single prior.

We explore prior robustness by using a version of variational preferences( [Maccheroni et al., 2006])

for

Remark 11.2

Axiomatic developments of decision theory in the presence of risk typically do not produce the functional form for the utility function. That requires additional considerations. An analogous observation applies to the axiomatic development of variational preferences by [Maccheroni et al., 2006]. Their axioms do not inform as to the how to capture the cost associated with search over alternative priors.

Remark 11.3

The variational preferences of [Maccheroni et al., 2006] also include preferences with a constraint on priors:

The more restrictive axiomatic formulation of [Gilboa and Schmeidler, 1989] supports a representation with a constraint on the set of priors. In this case we use standard Karush-Kuhn-Tucker multipliers to model the preference relation:

11.7.1. Relative entropy divergence#

Suppose we use

Solve the Lagrangian:

This problem separates in terms of the choice of

Solving for

Thus

Imposing the integral constraint on

provided that the denominator is finite. This solution induces what is known as exponential tilting. The baseline probabilities are tilted towards lower values of

This minimized objective is known to depict be a special case of smooth ambiguity preferences initially proposed by [Klibanoff et al., 2005], although these authors provide a different motivation for their ambiguity adjustment. The connection we articulate opens the door to more direct link to challenges familiar to statisticians and econometricians wrestling with how to analyze and interpret data. Indeed [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2013] also adopt a robust statistics perspective when exploring smooth ambiguity aversion preferences. They use constructs and distinctions of the type we explored in Chapter 1:Laws of Large Numbers and Stochastic Processes in characterizing what is and is not learnable from the Law of Large Numbers.

11.7.2. Robust Bayesian decision problem#

We extend Decision Problem (11.1) to include prior robustness by introduce a special case of a two-player, zero-sum game:

Game 11.4

Notice that in this formulation, the minimization depends on the choice of the decision rule

For a variety of reasons, it is of interest to investigate a related problem in which the order of extremization is exchanged:

Game 11.5

Notice that for a given

is additively separable and does not depend on

The two decision games: (11.11) and (11.12) essentially have the same solution under a Minimax Theorem. That is the implied value functions are the same and

A robust Bayesian advocate along the lines of [Good, 1952], view the solution, say

11.7.2.1. A simple statistical application reconsidered#

We again use the model selection example to illustrate ambiguity aversion in the presence of a relative entropy cost of a prior deviating from the baseline. Since the Minimax Thoerem applies, we focus our attention on admissible decision rules parameterized by thresholds of the form (11.8). With this simplification, we use formula (11.10) and solve the scalar maximization problem:

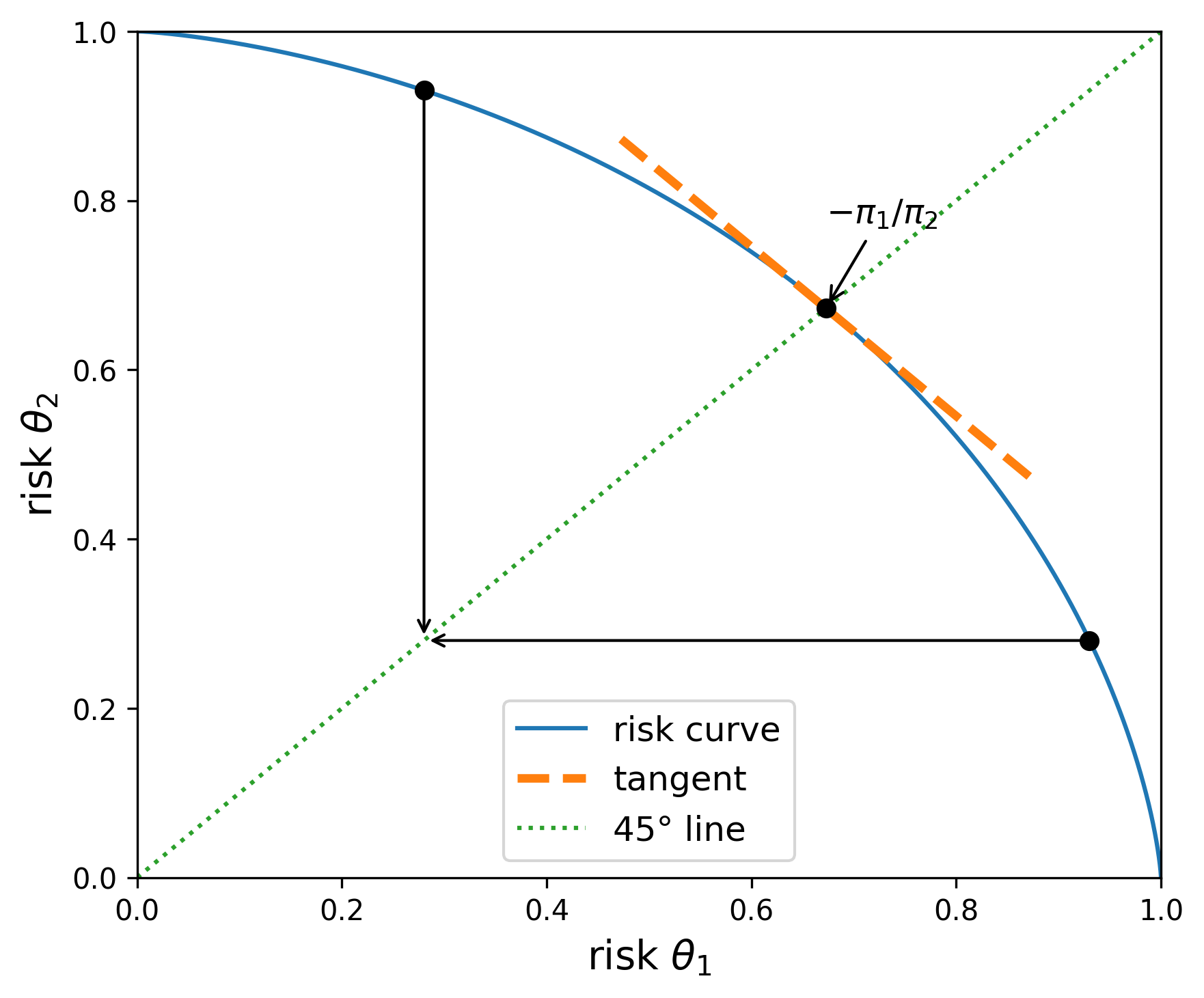

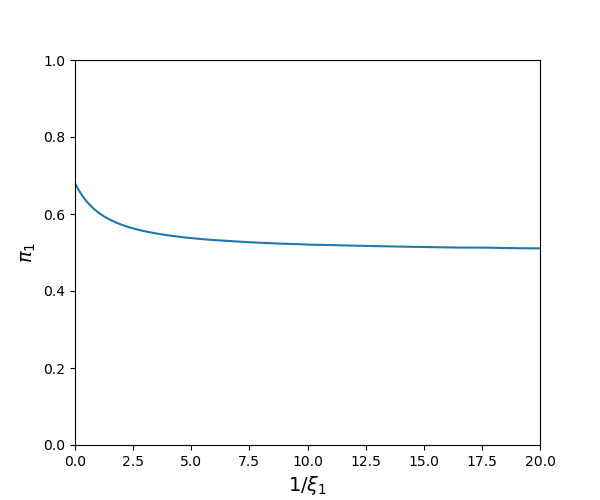

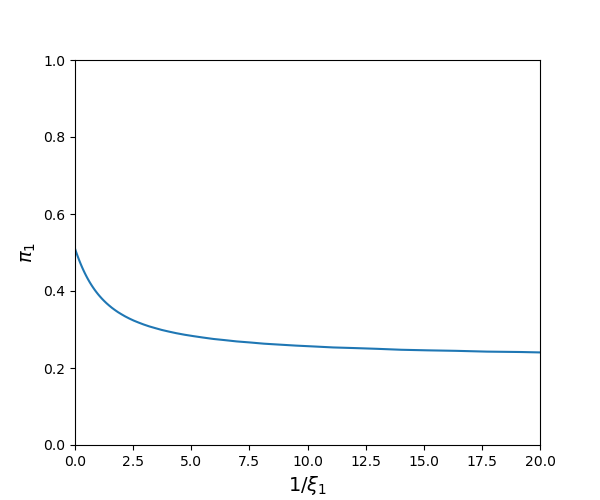

Two limiting cases are of interest. When

for

is satisfied.

When

Graphically, the objective for any point to the left of the 45 degree line from the origin equals the outcome of a vertically downward movement to that same line. Analogously, the objective for any point to the right of the 45 degree line from the origin equals the outcome of a horizontally leftward movement to that same line. Thus the maximizing threshold choice of

Fig. 11.3 The blue curve gives the upper boundary of the feasible set of risks. The utility function parameters are given by

Fig. 11.4 The blue curve gives the upper boundary of the feasible set of risks. The utility function parameters are given by

For positive values of

Fig. 11.5 Minimizing prior probabilities for

Fig. 11.6 Minimizing prior probabilities for

The two-model example dramatically understates the potential value of ambiguity aversion as a way to study prior sensitivity. In typical applied problems, the subjective probabilities are imposed on a much richer collection of alternative models including families of models indexed by unknown parameters. In such problems the outcome is more subtle since the minimization isolates dimensions along which prior sensitivity has the most adverse impacts on the decision problem and perhaps most worthy of further consideration. This can be especially important in problems where baseline priors are imposed “as a matter or convenience.”

11.8. Using ambiguity aversion to represent concerns about model misspecification#

Two prominent statisticians remarked on how model misspecification is pervasive:

“Since all models are wrong, the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong. It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad.” - Box (1976).

“… it does not seem helpful just to say that all models are wrong. The very word ‘model’ implies simplification and idealization. The idea that complex physical, biological or sociological systems can be exactly described by a few formulae is patently absurd. The construction of idealized representations that capture important stable aspects of such systems is, however, a vital part of general scientific analysis and statistical models, especially substantive ones …” - Cox (1995).

Other scholars have made similar remarks. Robust control theorists have suggested one way to address this challenge, an approach that we build on in the discussion that follows. Motivated by such sentiments, [Cerreia-Vioglio et al., 2025] extend decision theory axioms to accommodate misspecification concerns.

11.8.1. Basic approach#

To focus on the misspecification of specific model, we fix

and denote the set of all such

Observe that

where we assume

and

We use density ratios to capture alternative models as inputs into divergence measures. Let

We use this divergence to limit or constrain our search over alternative probability models. In this approach we deliberately avoid imposing a prior distribution over the space of densities (with respect to

Preferences for model robustness ranks alternative prize rules,

for a penalty parameter

11.8.2. Relative entropy divergence#

This approach to model misspecification has direct links to robust control theory in the case of relative entropy divergence. Suppose that

Remark 11.4

Robust control emerged from the study of optimization of dynamical systems. The use of the relative entropy divergence showed up prominently in [Jacobson, 1973] and later in [Whittle, 1981], [Petersen et al., 2000] and many other related papers as a response to the excessive simplicity of assuming shocks to dynamical systems that were iid and mean zero with normal distributions. [Hansen and Sargent, 1995] and [Hansen and Sargent, 2001] showed to how to reformulate the insights from robust control theory to apply to dynamical economic systems with recursive formulations and [Hansen et al., 1999] used this ideas in an initial empirical investigation.

When we use relative entropy as a measure of divergence, we have the ability to factor likelihoods in convenient ways. Recall that partitioning of

Add to this a factorization of

Let

Using these factorizations, the relative entropy may be written as:

where the second term only features integration over

Rewrite the expected utility function in (11.13) with an inner integral:

Notice that both the formulas (11.15) and (11.16) scale linearly in

11.8.3. Robust prediction under misspecification#

A decision rule is chosen to forecast

where the probability distribution over the

We find the robust forecasting rule by solving Game (11.17). We first solve the inner minimization problem which is given by:

To compute this objective, two exponentials contribute to this objective: one from the normal density for

where

The first term in the square brackets is the logarithm of a normal density with mean

Given this calculation, the outcome of the minimization problem can be rewritten as

Maximizing with respect to

where the inequality follows from the concavity of the

Thus for this example the robust prediction is to set

11.9. Robust Bayes with model misspecification#

To relate to decision theory, think of a statistical model as implying a compound lottery. Use

11.9.1. Approach one#

Form a convex, compact constraint set of prior probabilities,

11.9.2. Approach two#

Represent preferences over

Note that this approach uses a scaled version of a joint divergence over

The associated decision problem is:

Game 11.6

Remark 11.5

In Section Robust prediction under misspecification we studied a prediction problem under misspecification and established the conditional expectation under the base-line model is “robust.” Now suppose there is parameter uncertainty in the sense that we have multiple specifications of the pair

This objective adjusts for likelihood (or model) uncertainty but not prior uncertainty. The conditional expectation uses the probability measure;

Consider the special case in which

Joint densities can be factored in alternative ways. In solving the robust decision problem, a different factorization is more convenient. We focus on the case in which

Notice that the last term in the factorization depends only on

and posterior misspecification using

Additionally, we may alter the density

in an analogous way. While this latter exploration will have a nondegenerate outcome, it will have no impact on the robustly optimal choice of

Thus the decision maker may proceed with constructing a robustly optimal decision rule taking as input the posterior distribution defined on a parameter space

Finally, suppose that

we use

where

[Chamberlain, 2020] features this as a way to formulate preferences with uncertainty aversion.

In many applications it will be of considerable interest to allow for

11.10. A dynamic decision problem under commitment#

So far, we have studied static decision problems. This formulation can accommodate dynamic problems by allowing for decision rules that depend on histories of data available up until the date of the decision. While there is a “commitment” to these rules at the initial date, the rules themselves can depend on pertinent information only revealed in the future. Recall from Chapter 1, that we use an ergodic decomposition to identify a family of statistical models that are dynamic in nature along with probabilities across models that are necessarily subjective as they are not revealed by data.

We illustrate how we can use the ideas in this “static” chapter to study a macro-investment problem with parameter uncertainty.

Consider an example of a real investment problem with a single stochastic option for transferring goods from one period to another. This problem could be a planner’s problem supporting a competitive equilibrium outcome associated with a stochastic growth model with a single capital good. Introduce an exogenous stochastic technology process that has an impact on the growth rate of capital as an example of what we call a structured model. This stochastic technology process captures what a previous literature in macro-finance has referred to as “long-run risk.” For instance, see [Bansal and Yaron, 2004].[8]

We extend this formulation by introducing an unknown parameter

The exogenous (system) state vector

for a given initial condition

For instance, in long-run risk modeling

one component of

and another component is given by:

At each time

Similarly, we consider a recursive representation of capital evolution given by:

where consumption

for a pre-specified initial condition

Both

In this intertemporal setting, we consider an investor who solves a date

While the initial conditions

Include divergences, one for the parameter

as a measure of divergence and scale this by a penalty parameter,

In this model, the investor or planner will actively learn about

11.11. Recursive counterparts#

We comment briefly on recursive counterparts. We have seen in the previous chapter how to perform recursive learning and filtering. Positive martingales also have a convenient recursive structure. Write:

and

By the Law of Iterated Expectations:

Using this calculation and applying “summation-by-parts” (implemented by changing the order of summation) gives:

In this formula,

is relative entropy pertinent to the transition probabilities between date

where date

Remark 11.6

Our discounting of relative entropy has important consequences for exploration of potential misspecification. From (11.19), it follows that the sequence

is increasing in

gives an upper bound on

for each

Taking limits as

If the discounted limit in (11.21) is finite, then the increasing sequence (11.20)

has a finite limit. It follows from a version of the Martingale Convergence Theorem (see [Barron, 1990]), that there is limiting random nonnegative variable

Observe that in the limiting case when

As an alternative calculation, consider a different discount factor scaling:

The limiting version of this measures allows for substantially larger set of alternative probabilities and results in limiting characterization that is used in Large Deviation Theory as applied in dynamic settings.

Remark 11.7

To explore potential misspecification [Chen et al., 2020] suggest other divergences with convenient recursive structures. A discounted version of their proposal is

for a convex function

11.12. Implications for uncertainty quantification#

Uncertainty quantification is a challenge that pervades many scientific disciplines. The methods we describe here open the door to answering the “so what” aspect of uncertainty measurement. So far, we have deliberately explored examples that are low-dimensional to illustrate results. While these are pedagogically revealing, the methods we described have all the more potency in problems with high-dimensional uncertainty. By including minimization as part of the decision problem, we isolate the uncertainties that are of most relevance to the decision or policy problem. This may open the door to incorporating sharper prior inputs or to guiding future efforts aimed at providing additional evidence relevant to the decision-making challenge. Furthermore, there may be multiple channels by which uncertainty can impact the decision problem. As an example consider an economic analysis of climate change. There is uncertainty in i) the global warming implications of increases in carbon emissions, ii) the impact of global warming on economic opportunities, and iii) the prospects for the discovery of new, clean technologies that are economically viable. A direct extension of the methods developed in this chapter provide a (non-additive) decomposition of the channels of uncertainty. By modifying the penalization, uncertainty in each channel could be activated separately in comparison to activating uncertainty in all channels simultaneously. Comparing outcomes of such computations reveals which channel of uncertainty is most consequential to the structuring of a prudent decision rule.[11]